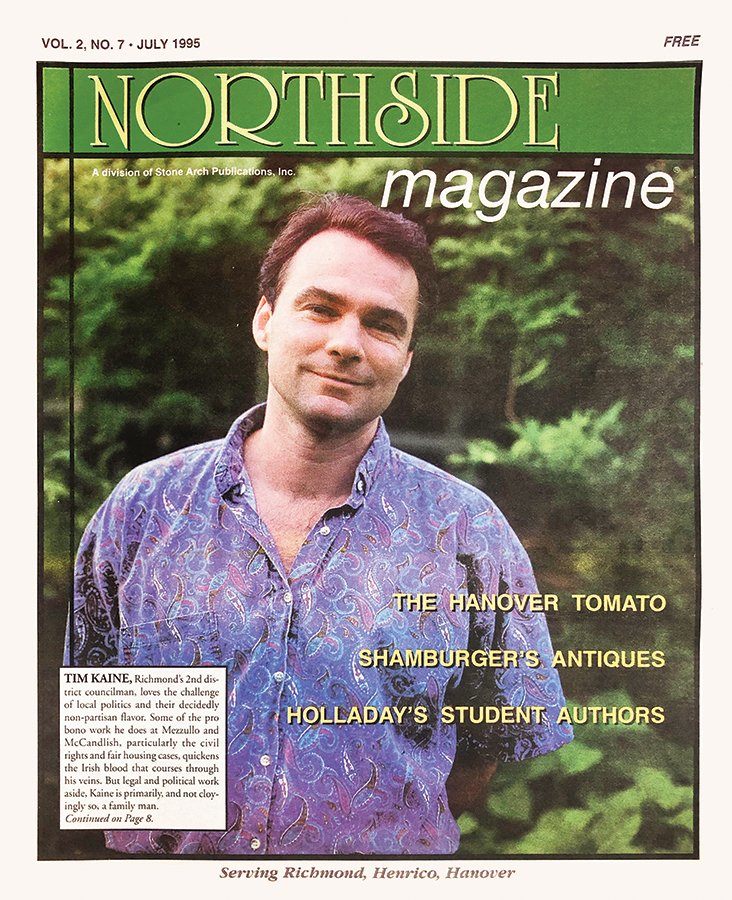

Original cover from July 1995.

Citizen Kaine

by Charles McGuigan 07.1995

Councilman Tim Kaine is a man of the people. His father ran an iron-working shop in the stockyards of Kansas City, and as a high school student at Rockhurst, a parochial school, Tim traveled to Honduras to the site of a Jesuit mission. That changed his life for good and all.

After high school Tim earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and then went to Harvard Law School. But instead of getting his law degree right away Tim took a year off and returned to El Progresso, Honduras where he taught basic carpentry and welding skills to impoverished teenagers.

“I remember how strange it seemed one day with these seventy Honduran students banging and sawing away so that I couldn’t even hear myself think,” Tim remembers. “Here I was in a place as far removed from Harvard Law School as you could be on the same planet.”

In that alien land, Tim began to notice traits among people that surprised him. “The whole experience really turned me around,” he says. “There was this incredible coexistence of poverty with tremendous faith, happiness and spirit.” When he returned stateside it often struck him that his countrymen who had everything materially seemed to suffer a general malaise. “But there was none of that in Honduras, even though the people were extremely poor,” he says.

Tim recalls a specific example at Christmas one year as he traveled on mule through the mountains accompanied by a Jesuit. They came upon the simplest, meanest hut Tim had ever seen. “The guy who lived there was sick, malnourished, but as Father Patricio and I left, this man gave us this big bag of food—gourds and fruits,” Tim tells me.

As the pair left the village the priest turned to Tim and said, “You know, Tim, it takes a real humble person to accept food from a poor person.” Those were Tim’s exact thoughts at that moment.

“It’s as if the priest was reading my mind,” he says

The Jesuits in Honduras, because of their diligence in working with the poor, became folk heroes to Tim. He remembers one in particular, a priest by the name of Guadaloupe Carney. Tim had never seen him.

“He was a sort of spectral presence,” says Tim. “He was thrown out of Honduras and moved to the mountains of Nicaragua. He was a liberation theologian and simply preached to the workers in the banana plantations owned by United Fruit.”

Tim says Father Carney often preached with New Testament stories as a basis. He told banana plantation workers that they never had to look at themselves as Samaritans or other second-class citizens.

One evening, Tim got the chance to finally meet Father Carney. “It was an enlightening time, one that I’ll never forget,” he says. A year later, Father Carney slipped across the border into Honduras and was apprehended by local militia and summarily executed. “I admired the traits of these people,” says Tim. “What they did for the sake of justice. And I learned very much from them.”

It may have been the Jesuits who inspired Tim to do both the civic work and pro bono legal counsel he is known for, which stamped him as a liberal during his campaign to win the Second District City Council seat in Richmond. His association with Housing Opportunities Made Equal (he ended up winning for that organization one of the largest settlements in history against a company that practiced redlining) and his service in El Progresso raised the eyebrows of some of the older powers-that-be in the Richmond area, including the owners of a food store chain that is known for its adherence to extreme conservative views. But Tim never toned down his rhetoric; he stayed true to his beliefs.

“I am a liberal and proud of it,” he says. “I am a liberal in the classical sense of the word, in terms of liberty and the ideals of Thomas Jefferson.” Tim is something of an iconoclast, and therefore impossible to label. “You might use personalism to describe me,” Tim says. “I do not believe, for instance, that government should crush people. I‘m not a big institution person and am very much in favor of decentralization. On fiscal issues I tend to be very conservative. And I am distrustful of all big institutions. I favor giving economic power to small businesses.”

I ask him if he would consider a higher political office, perhaps following in the footsteps of his father-in-law, the former Governor Linwood Holton, and Tim smiles. “Well I’d like to serve on Council for another four or six years,” he says. “I don’t see myself running for the Senate. Not at this time. I guess there’s part of me that would like to see my wife living in the Governor’s Mansion again.” And then he changes the subject.

When he begins talking about some of the cases he’s tried, Tim becomes animated. He smiles when he talks about settlements for the underdogs, shakes his right fist with jubilance when he describes courtroom victories.

Consider Saunders versus GSC (General Services Corporation). GSC owns a number of apartment complexes in Richmond and elsewhere. “This was the first one of these cases tried in the country,” says Tim. And we won, setting a precedent.” At the time of the case in 1987, GSC’s primary advertising was through the distribution of a forty-page brochure. “This brochure featured about four hundred people,” Tim explains. “But only one was an African-American.” And GSC did not distribute the brochure at primarily black universities like Virginia Union. “They were distributing at predominantly white institutions like VCU and U of R,” Tim says. Judge Robert R. Merhige ruled in favor of the plaintiff, and found GSC guilty of discriminatory intent. But on the eve of the trial, GSC came out with a new brochure that featured blacks and whites alike. “That brochure, incidentally, became a model of a non-discriminatory brochure,” he says.

One of the oddest cases Tim ever tried was down in Mecklenberg County and it had all the gothic intrigue of a good Southern novel. An older woman by the name of Judy Cox, who was something of an animal rights activist and worked part-time at a correctional facility, charged the local government was not properly tending to stray animals. The hierarchy at the Baskerville Correctional Institute were “tight with the Board of Supervisors,” according to Tim.

“Some of the state investigators dragged a local lagoon and found hundreds of dog skeletons, each with a single bullet through the skull,” Tim says.

Meanwhile, Judy Cox was having trouble with stray dogs roaming her property. She called the game warden, requesting a dog trap and was told that it would be dropped off at the correctional facility. One day, after work, Judy asked for the dog trap. A guard gave it to her.

A few days later Judy received a call from the correctional facility and was asked if she had stolen a dog trap. “Judy was completely shattered by this,” Tim remembers. She was arrested that afternoon by state police and local papers carried on their front pages banner headlines. COUNTY SUPERVISORS BLAST ANIMAL RIGHTS ACTIVIST, read one, according to Tim. Judy was subsequently fired.

As it turned out, supervisors conspired with employees of the correctional institute. There were two guards in the room when Judy picked up the dog trap and though one clamed she stole it, the other would not sway from the truth. “This one guard, a woman, refused to lie under oath,” says Tim, who proved in court that elected officials and employees of the correctional facility were guilty of charges of conspiracy and violation of civil rights. “Public reactions were printed in all the newspapers,” Tim says. “The case was settled positively in favor of the client.” He pauses, then adds with a grin: “We had to call it the Hounds of the Baskerville.”

In the telling of these war stories, Tim can’t contain his enthusiasm. Each case he tackled with gusto, and much of his work has been done pro bono. Every year he donates at least two hundred and fifty hours of legal work, and this year the Richmond Bar Association presented him with the Pro Bono Publico Award. This award, incidentally, is the only framed document that adorns his office. There are no framed degrees or other certificates, just this one award that notes his work for those who cannot afford legal counsel.

That says a lot about this man. You could easily see him leading the Commonwealth. And, someday, perhaps, even the Nation.

Tim Kaine with harmonicas.

Editor’s Note:

This was our cover story in July of 1995, just eight months after our inaugural issue. Tim later became Mayor of Richmond, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, Governor of Virginia, US Senator (an office he still holds), and the 2016 Democrat nominee for Vice President of the United States. I have known Tim now for more than 25 years, and in that time he has been consistent in his political philosophy. Unlike the vast majority of other politicians I have interviewed over the years, Tim has not wavered in his foundational values, for he is a true statesman.

The first interview I ever did with him was on his back porch where we talked late into the night, nursing a few bottles of Yuengling. On the front porch of that same house in Laburnum Park, I visited Tim in May of 2020, and we talked at length about the pandemic and other pressing issues. This was nine days before the sadistic murder of George Floyd.

Sitting up on the top step, dressed in faded blue jeans and a maroon knit shirt, Senator Kaine talked about the state house in Michigan, which was closed that day because of threats made against Governor Gretchen Whitmer.

“The archetypal picture recently is the one of the people in the Michigan capitol yelling in the faces of State Police,” he says. “And you think about somebody with no mask on who potentially has coronavirus intentionally trying to infect somebody by standing six inches away and yelling in their face. I’m outraged when I see those pictures.”

When I asked if he’d ever seen anything like this before, he reminds me that he spent seventeen years as a civil rights lawyer before going into politics. “I think the election of a President Obama says something very true about who America is, but the election of a President Trump also says something very true about who America is,” he said. “I don’t think these folks are the majority, but if you don’t understand that there are some hate currents that are in this country, then you don’t really understand the full nature of who we are.”

I had asked Tim earlier in the interview if he’d play a tune on the harmonica. He brought out a number of them, spread them out on the brick stoop, then selected one, and played “This Land Is Your Land”, and even sang several verses of that folk classic. (If you’d like to see the video of Tim playing Woody Guthrie’s timeless anthem, follow this link to our YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6GyGLIfm44)

Tim and his wife Anne Holton have now sold their home on Laburnum Park Boulevard, but have no intention of leaving the city. "Anne and I have decided to sell our Richmond home of thirty years and move downtown,” he said. “We love our house, neighborhood, and neighbors. But now that we're empty nesters, we'll downsize. We're excited to stay in the heart of RVA."