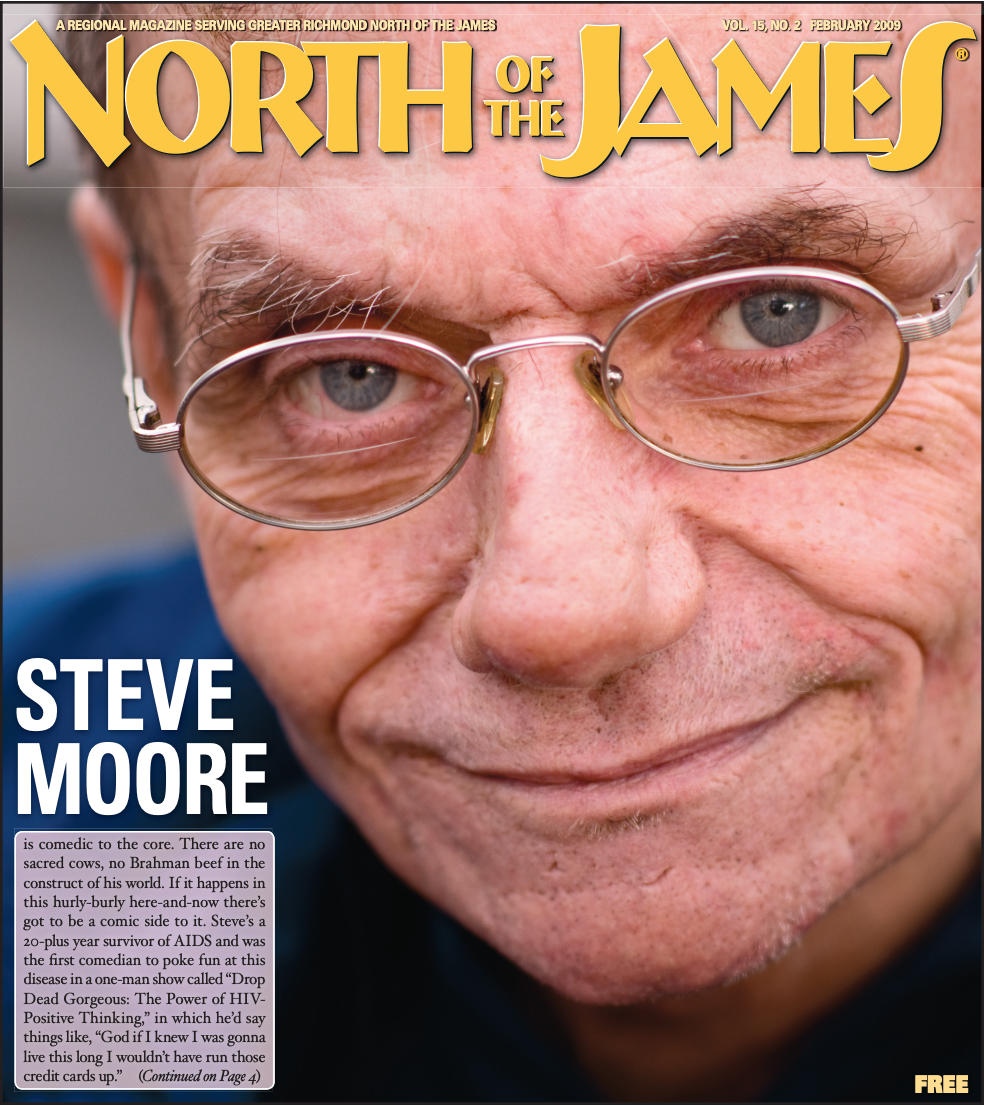

Steve Moore: The Joke’s On Us

by Charles McGuigan 2009

This story about Steve Moore, a comedian and a writer, was published in February of 2009. For years after returning from California, Steve lived in Richmond, and on May 24, 2014, at the age of 59, he passed away in his native Danville, Virginia.

Charmed lives lack for something. If you’re born in a state of nirvana or somehow privileged as a member of the elect, what’s the point? It’s only through trials, and sometimes the very worst kind, that we learn if we’ve got the right stuff. And that right stuff invariably seems to be the ability to laugh death and disaster in the face, send it on its way to where it rightfully belongs. That’s what Steve Moore owns.

Stevens Spencer Moore, the man with three last names, was born in Danville, Virginia to Skeets and Wilma, and raised in a fundamentalist tradition. Skeets worked at Liggett-Meyers Tobacco Company; Wilma was a line worker at Dan River Cotton Mill. They later bought a little hot dog stand called the Dairy Hart, which is where Steve worked through high school.

We’re sitting in his living room which is thickly peppered with nostalgic bric-a-brac, remnants of a former era. Steve tells me that as soon as he graduated from high school he dusted Danville off his heels and moved to Richmond where he began studying theater at Virginia Commonwealth University.

After two years at VCU, Steve headed up to the Big Apple. “At VCU you lie on the floor and you breathe and you learn exercises and you build sets,” says Steve. “And I went, ‘You know I’m not going to be a teacher, and if I want to be an actor I’m going to get out of here.’ It’s not like I could be up for a sitcom in LA and they’d go, ‘Whoa, a BFA in acting from VCU. Why didn’t you say so? It’s your part.’ They don’t care where you went to school, they want to see what you’ve done.”

Things didn’t go so well in New York. About the only job Steve could land was playing piano at a silent movie house in Brooklyn, so six months later he returned to Richmond and went to work as an entertainer at Kings Dominion.

After two months at Kings Dominion, Steve had managed to save $600 and with this modest bankroll headed west. “In California I was like a kid in candy store,” he says. “All the queers, the most beautiful men in the world.”

In LA he delivered the daily paper, and worked as a busboy and bartender at the Old World Restaurant in Hollywood. And then he started playing piano for Dee Anne McEnistry. They did an act called Beauty and the Burger, and later played the Ice House in Pasadena, opening for Gallagher.

Things got better. Dee Anne’s boyfriend was a member of a comedy team called Granite and Pallazo. Steve played piano for them which led to a job at the Comedy Store. “I saw how so many comedians got work on sitcoms and TV shows and when they worked they made good money,” Steve says. So Steve changed his plans of becoming an actor, and honed his skills as a comedian.

“I’d write and perform funny songs,” he says. “The first funny song I wrote was a parody of ‘He Touched Me’ and I wrote, ‘I Touched Me.’ And then I started talking to the audience from the piano and that parlayed into me emceeing a lot of times. And all of a sudden I had this act I could do anywhere. So I pretty much crawled my way to the middle. Opening act, middle act, head liner.”

Working at the Comedy Store, observing stand up comics night after night, taught Steve the essentials of the trade. And he learned, too, that many comedians made their real living as warm up acts for sitcoms that were taped live.

Steve fell right in step. “I was really good at playing with an audience because of those years at the Comedy Store,” he says.

He worked on ‘Designing Women’ for four years, then ‘Roseanne’, on an off, for five years. Of Roseanne Barr, Steve says, “I knew her when she first came to town. I saw her when she auditioned to be at the Comedy Store. I used to go play bingo with her and go hang out with her and the kids. And then she did the ‘Tonight Show’ and she was like this huge star. It happened overnight. Trailer trash with millions and millions of dollars. It makes you a little crazy.”

Roseanne, as you might guess, wasn’t the easiest person in the world to work for, but the pay was good—about $1,500 a pop. “I’d do the warm-ups for her show and she fired me five times, I guess,” Steve remembers.

Shortly after he’d been fired for the fifth time, Roseanne’s producer called Steve. “It was the last episode of the ‘Roseanne’ sitcom and Al Lowenstein called me and said, ‘You know she’s really vulnerable and wants her old friends around her and we wondered if you would come and do the last warm-up for the show.’ And this is where I learned the power of the word no. I thought about it and said, ‘Al, you know what, she’s fired me five times and I’m really not interested. Five is enough.’”

A couple hours later Lowenstein called Steve back. He offered him $5,000 for one show. Steve told him, “I’ll see you at three.”

One of the hardest days Steve ever had was in 1989 as he was preparing for an interview with his agent. He had just been tested for AIDS. “I had my eight-by-ten pictures and my resumes with me and I swung by the clinic to get test results,” he says. “It came out positive.”

He pulled off the interview without a snag, in a state of absolute denial. But later at home things fell apart. He called his folks back in Danville and started crying into the receiver. His mother, Wilma, cried as well. “All I knew about it was that it was killing people and there was no cure and there was only one pill that you could take,” Steve tells me. “So I am truly one of the lucky ones. I mean I went to funerals every week”

Health insurers then were pretty much what they are now—slime bags and miscreants. Steve found out that his co-pay for this new wonder drug was much higher than he could ever afford. But there were physicians who remembered their Hippocratic oath. “I went to this doctor and told him my story and he gave me a big brown bag full of AZT,” says Steve. “And doctors would do that. And so that kept me alive.”

Out of this immense personal tragedy, Steve drew on humor, gallows humor, the darkest and most rib-tickling sort that works its way out from the marrow. He began making jokes about AIDS and HIV, coming out of the closet, and breaking new comedic ground.

“All of a sudden I was the AIDS guy,” Steve says. “People would say, ‘Oh my God this guy has AIDS. He’s a comedian and he’s telling jokes about it. I did every talk show that you could imagine.”

He tells a few jokes from that time in rapid fire. “Well my parents in Virginia think HIV stands for homosexuals in Virginia,” he says. “I started talking about it like it was no big deal. And then I’d say, ‘AIDS – God, I hope I never get that again. You guys got to be careful out there – don’t mess with me or I’ll open a vein and take out the whole front row.’”

All of this led to an hour-long HBO special that gave Steve instant international recognition, but more than that, it allowed him to be who he really was and it gave him a sense of self that he had never known before.

Though the HBO special didn’t make Steve rich, it did give him a good chunk of change so with money in hand, he decided to move back to Virginia.

Not long ago, grief dealt Steve a knock out blow. Dale Moore, his brother and only sibling, was found dead in the James River. He was an avid kayaker and knew the waters well.

“It’s always been me, my straight older brother’s and my mom and dad,” says Steve, lowering his voice. “We’ve always loved each other so much. Now I’m the one that has to step up to the plate. Because he’s gone. And he’s got the three kids. His daughter’s having a baby today that he’ll never see that baby.”

He remembers vividly the day his brother body was found on a muddy shore of the James River. “It was horrific,” he says. And the authorities and a local television station made it even worse.

One of the local news networks botched things badly. They flashed a photo of Dale and announced that his corpse had been discovered. Dale’s children, who didn’t yet know their father was dead, saw the news clip. “The kids start screaming,” Steve recalls. “And then detectives come over and one says, ‘Is this your father’s watch?’ It was a picture of his dead arm and the watch. And then they ask, ‘Is this your father’s necklace?’ And the kids are screaming, ‘Yes, yes, yes.’ All of us went through a tailspin with that.”

He tells me a little bit about his parents and the love they’ve always shared as a family. Many years back, Steve, while visiting from California, decided to tell his parents that he was gay.

“So Dale took Skeets out to the garage and I told Wilma in his bedroom,” Steve says. “And I started crying, ‘Mom I’m queer,’ I said. And she said, ‘You see me crying? You think I love you any less?’” At the same exact moment Dale was breaking the news to Skeets. “And this is what Skeets said,” Steve tells me. “‘Well, I reckon they’re born that way.’ Just like that, and that was it.” He snaps his fingers.

Steve minces no words, does not try to paint life in rosy hues. No lies; no denial. He

tells the clouded truth, examines the grayness of our reality. Perhaps that’s why his routines always worked so well. Maybe that skewed path to truth is the essence of all great comedy.