Alleys: Roads Less Traveled, Part 2

by Charles McGuigan 06.2023

photos by Rebecca D’Angelo

Rick Bridgeforth who converted an entire alley area into a botanical garden.

Early in the morning, with his dog in tow, Rick Bridgeforth pushed through the gate in his backyard which led him into the vast alley space that runs between Grove and Hanover just off of Robinson. In the dim autumn light he could make out a handful of people seated before the assortment of tables—some of concrete, others of wood—behind World Cup Coffee. These folks, the uber hipsters of their era, would cavalierly toss plastic stirrers and Styrofoam cups and plastic forks and spoons onto the ground. As one young man balled up a napkin in his hand and prepared to throw it, Rick called him out on it, and asked him and the others if they wouldn’t mind using one of the conveniently placed trash cans on this makeshift patio. A shaking of heads, slight laughter. Mainly though he was ignored with a searing silence. Then one afternoon, as he walked his dog, it came to him in a not-so-blinding flash. And he mouthed these words: “If you make it pretty, people won’t litter.”

And for the next 38 years, that’s exactly what Rick has done with the alley area behind his home on Hanover Avenue.

About a month and a half ago, my son Charles and I came upon this alley in our wanderings through the Fan. Rick was out there, along with two women. It was a warm Sunday afternoon, and the three of them were enjoying beverages, surrounded by a veritable botanical garden that Rick had created over the years. The sheer size of the garden he created in the footprint of brick garages that once stood there amazed me. As we talked I was identifying flower after flower—larkspur, gigantic delphiniums, foxglove, summer flox, sweet William, iris, helleborus hydrangea, and scores of others—and the colors were vibrant and dazzling. All of it was planted in a fashion that called to mind the impressionistic landscape design of Gertrude Jekyll, an English gardener whose handiwork had a painterly quality.

He invited us to sit and enjoy the garden, and began to tell us how he began the garden in the first place. “I would get mad every day walking my dog and picking up everybody’s coffee stirrers and coffee cups,” Rick told us. “So I decided to make it pretty. That’s how it started began, and it started in my parking place and just took over. It just expanded little by little. As soon as it became pretty, the littering stopped.”

At that time, a garage, which Rick had rented, stood in the middle of the parking area bordered by the alleys. He stored his tools inside the garage and on the roof kept seven bee hives. About twelve years ago a storm took down the giant willow oak that grew in that alley. When it fell, the tree crushed the garage, and though Rick lost his bee hives (he has three hives now in his backyard), he was able to expand his plantings in the alley. “After the garage collapsed, I got rid of all the bricks, made those columns there,” he said, gesturing toward a pair of vine-clad columns. “And I put in the apple tree.”

The young woman sitting next to Rick held up her iPhone and began scrolling through dozens of pictures. She invited me to take a look. Each photo captured waves of colors—reds and pinks, yellows and purples. “That’s what this garden looked like back in April,” she said.

Rick nodded. “I just ripped up 3000 tulip bulbs, last year it was 4,000,” he said. I plant them in the fall and they sit through the winter. Then after they bloom I rip out the tulips and throw them away, and the perennials start to come in.”

Rick told me that he had attended William and Mary, studying French and pre-med. But his heart wasn’t in it; it was something his father prodded him in to doing. So when his father passed away, Rick decided to chase his own dream. “When he died, I said, ‘I can do whatever I want now,’” he said. “I became a hairdresser. I moved out to LA and studied at Vidal Sassoon in Hollywood.”

Section of Rick Bridgeforth's alley garden.

Back in Richmond he would open his own hair salon, a shop called Wilma Ray at 7 West Cary. “I had that for ten years, and then the Jefferson asked me to open a salon there, so I opened the salon at the Jefferson and had that for twenty years,” Rick said. “I also ran the florist shop at the Jefferson.”

That was just one of his professions, though. He also did a fair amount of landscape design, putting the finishing touches on fairly large gardens.

“The landscaper would put all the trees and shrubs in and then I would say, ‘We need this over here, that over here, fifty of those, six of these,’ And it made it look like it was born there,” said Rick. “A lot of the people that I used to design for wanted their homes and gardens in magazines. I call what I did, adding the charm.”

Rick’s fascination with things that grow in the good earth goes all the way back to his early childhood. “I’ve been doing this since I was six years old,” he told me. “I had a rose garden with one grandmother, and I helped my other grandmother with her vegetable garden.”

And here in this alley oasis that Rick has been perfecting for more than three decades, there is also a large vegetable garden that he also plants annually. On any given Sunday folks visit the garden, bringing wine and cheese and soaking up the sun and nature’s beauty. And that’s the day, Rick works in the garden, pulling weeds, tending his crops. “I don’t go to church,” he said. “This is my church.”

Before my son and I left, Rick Bridgeforth said this: “I just try to get everybody to make their alley look pretty. Since I first started the garden along this alley, it has spread to other alleys in the Fan.”

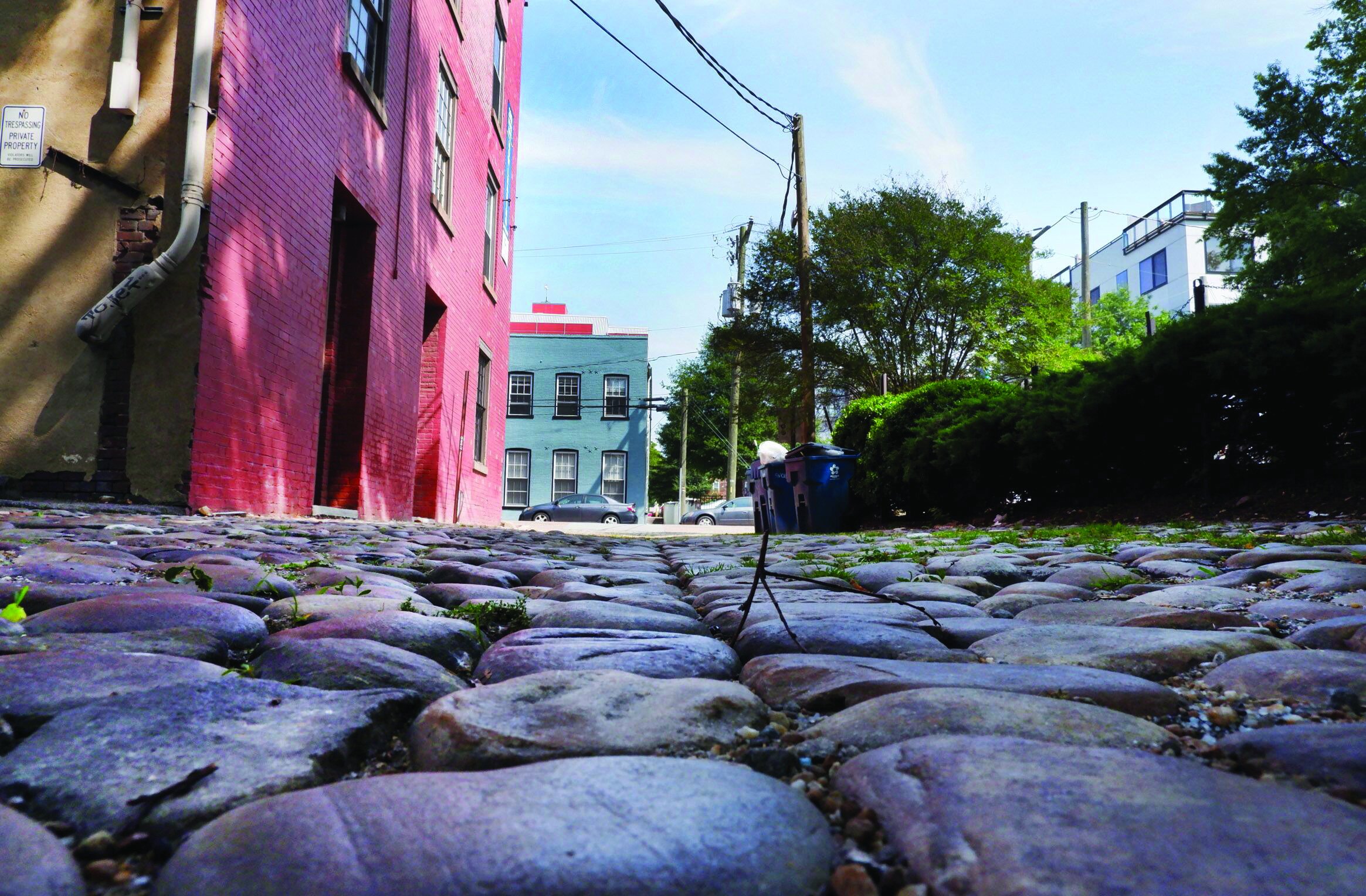

Actual cobblestone alley behind the Poe Museum.

Many of the alleys in downtown Richmond, the Fan, and Church Hill are lined with what many refer to as cobblestones. These are those rectangular or square blocks of gray granite and are probably more accurately called Belgian blocks or stetts. They were cut by stone masons who worked in any number of quarries along the James River. There was a time in the early 20th century that these Belgian blocks were shipped by rail to cities throughout the country.

But the very earliest cobblestones were not locally quarried. Many of them were rounded field stones that served as ballasts aboard ships sailing from England. Once those tall ships arrived at a port city like Richmond, the cobblestones were unloaded on the docks, and the cargo for the return trip—commodities like tobacco—were packed into the holds. These cobblestones were sold from the wharf and used to line the streets and alleys in America’s fledgling cities. There are few of these actual cobblestone alleys remaining in Richmond. There are several on Church Hill, and there was an expansive one near Rocketts Landing. But that was scraped away in the name of progress several years ago when that area was redeveloped. One of the most notable cobblestone alleys in the city is behind the Poe Museum in the 1900 block of East Main Street. It’s worth checking out.

Some alleys in Richmond actually bear names that are prominently posted like street signs. There’s Walnut Alley down in Shockoe Bottom between 17th and 18th Streets. And on the northern edge of Oregon Hill, between Cary and Cumberland, there’s Green Alley. One alley is named for an unconventional preservationist who was instrumental in saving many of Richmond’s historic buildings. Fittingly, the alley that runs behind Linden Row on East Franklin Street is named after this woman, Mary Wingfield Scott, who had purchased seven of the homes that make up this historic row, and then began restoring them to their former glory. And this group of homes is now considered the best surviving row of Greek revival architecture houses in the country. Mary Wingfield Scott was their personal savior.

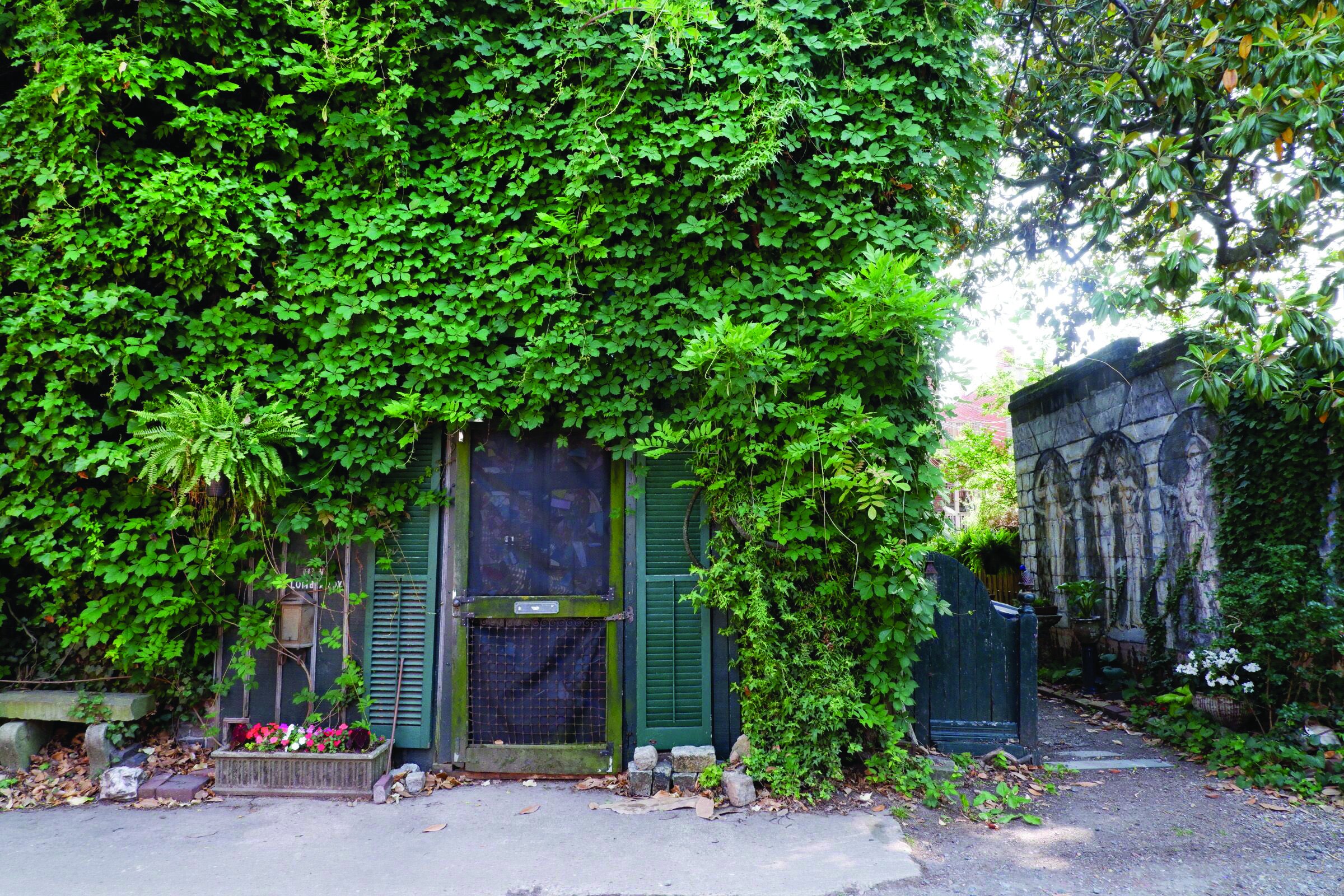

Richard Bland's carriage respository sheathed in Virginia creeper, wisteria and English ivy.

There is one man in Richmond who knows more about the city’s strange and frequently convoluted histories, large and small, than anyone else I know. He has salvaged hundreds of artifacts and relics and written records that reflect those histories. What’s more this man is a gifted painter whose work not only captures the beauty of our city, but acts as a sort of on-going chronicle of it. He’s also lived along alleys most of the time he has called Richmond home, which spans over half a century now. Richard Lee Bland lives in one of the most curious and largest alley structures in the Fan. It’s a two-story brick building, and its front elevation is completely covered by a veil of Virginia creeper, wisteria and English ivy. To the untrained eye, it could be mistaken for a carriage house. But it’s actually something different than that.

“My old place in the alley was a carriage repository,” Richard wrote. People in the early decades of the 20th century would hire drivers and “conveyances” from the repository. “My two doorways and windows open onto four connecting alleyways,” he added. “I've known a personal seclusion of carriage house living from the time of my renting a nearby carriage house dwelling in 1969. Views and sounds from the windows and the veranda overlooking the back alley most often are into the tops of trees—birds singing, squirrels in their acrobatic maneuvers, rabbits below silent in the bushes. Through my ivy covered lattice and trellis I can see brick-walled courtyards. These areas are shaded by tall elms and overhanging branches from a large oak.”

Richard then went on to write about the area of the city that has been his home for many years. “The Fan District west of Monroe Park had been a scattering of mansion estates known as the town of Sydney. This district is better known today as The Fan District due to the streets spreading into a fan shape around small triangular parks at the juncture of several streets . . .The interior of these city blocks and squares is a world to itself reminiscent of rural lanes, graveled stone on earthen alleys and granite pavers oriented to an east to west direction lined by brick carriage houses, verandas, sleeping porches, or shuttered windows, garages, brick arches, and ornate gateways, courtyards and gardens.”

Like many of us Richard has done his share of shopping along the alleys. “Over the course of years I am not alone in furnishing my home from Richmond's alleys with vintage discarded treasures,” he wrote listing scores of alley finds. Here’s a partial list. “A jukebox from a Union Hill alley, a large taxidermy mounted sailfish from a downtown alley, a circa 1840's plantation table with turned legs a block up my alley, a circa 1900 wooden restaurant booth on a Granby Street alley, a circa 1900 rusticated bent wood with split wood back and seat on my alley, ornate advertising signs off several alleyway, a circa 1870's plantation kerosene lamp encasement with large glass shade on a downtown alley, an embroidered tapestry and a middle eastern circular hammered brass squatting table with opening for a charcoal ‘fire bowl,’ hand-knotted oriental rugs, a splendid example of uranium glass platter and glass cup, discarded fossils and sea shells.” Richard had been invited to appear on the History Channel’s American Pickers, but declined the offer to preserve his privacy.

In Scuffletown Park, four-year-old Eleanor Bury trains a camera on her mom, Carlisle Wikinsoner, and Erin Soorenko, who also wields a camera.

Over the years I have found extraordinary pieces along our alleys, everything from original artwork to a Stickley end table (which I ended up selling for a huge chunk of change), and almost every piece of furniture in my home was rescued from an alley—an oak Morris chair, a walnut washstand with a pigeon-blood marble top, a golden oak barbershop mirror that I repurposed into a bookcase.

Friend and neighbor, Liz Scarpino, who contributed to last month’s cover story, wrote eloquently about alley finds: “Alleys in Richmond still represent a sort of street-level liberation to me — places of DIY potential, where I can glean from piles of ‘good garbage’ (as my sister, who often alley-shopped boroughs of New York City, calls it) to harvest awesome finds of tossed artwork, furniture, clothing, musical instruments, scrap lumber, old signage, you name it. No shame in it at all. Quite the contrary: my home/garden/wardrobe are filled with unique trash-to-treasure finds: some we mend or refurbish, some we repurpose or deconstruct entirely, some we save from a crushed-to-smithereens landfill fate just in the nick of time, as the garbage truck lumbers and clamors close. In this age of planned obsolescence, timber mafias, ecocidal clearcutting, and particle board put-it-together-yourself-and-wait-for-it-fall-apart crap from big box stores, who wouldn’t rather have quality, free, vintage stuff? Friends all over town alert me to particular castoffs, knowing I’ll likely have a look-see and might-could use something there. I feel like this practice has imbued our home with a true sense of place, a connection to community, our own unique mise-en-scène narrative, and a greener, multi-generational aesthetic that honors the material culture and history of Richmond neighborhoods.”

Another friend and neighbor, Rob Ullman, illustrator and graphic designer, had a thing or two to say about alleys. He’s a Buckeye by birth, and moved to Richmond 25 years ago, settling first over in the Fan. Here’s what he wrote: “Immediately upon receiving the keys to my apartment on Park Avenue, I became enamored and fascinated with the city’s extensive network of alleys. As the self-employed owner of a dog, I had hours to explore these urban shortcuts, and made use of every opportunity. Some of the alleys were so well-developed, with brick streets and fancy garages and carriage houses, and some were so wild and unkept, with little discernible rhyme or reason, at least to my historically ignorant eyes.

“Moving to Bellevue a few years later, I found the alleys different, but no less voluminous and interesting. These hidden passageways always seem to reveal the true personalities of the neighborhood’s residents, in ways that the front of the buildings cannot. From the messy and in-progress to the manicured and overmanaged, you can find out a lot about a person by observing their house from an alley.

“I’ve run literally HUNDREDS of miles through the Northside over the last two decades, as many behind the homes as in front of them. There is always something new to notice, something to catch the eye. Sometimes it’s a great idea for a new outdoor space, sometimes it’s a cool, discarded end table that would look great in my studio.”

Like Rob and many others, I too migrated from the Fan to Bellevue. And on the Northside the alleys are different. For one thing, many of them are paved with loose gravel, not Belgian blocks or bricks. But like all the alleyways throughout the city those in Bellevue have an air of enchantment and are filled with surprises from the pebble stone garage on the alley facing Holton Elementary, to a towering carriage house just off Lamont.

The country lane alley in Bellevue.

Across a guardrail along Stanhope there’s a dirt path that takes a deep dip toward a wider path that will take you along what looks for all the world like a country lane. Lined with towering trees and bushes and wildflowers and weeds, this path, which stretches a full half-mile to its conclusion at Crestwood Road, is actually one of the few alleys in Richmond vacated by the city decades ago. It has become a wild area where native flora and fauna flourish. I’ve spotted coyotes there, picked blackberries in late June, found a mass of jewelweed, caught a five-foot long black snake, which I later released. And I found the tail feather of a red-tailed hawk, and on the very same walk discovered a primary wing feather from a great horned owl. That was a lucky day.

A few years back we had a rescue dog named Forest who was all muscle, with a solid black coat except for a small white triangle just below his neck that gave him the appearance of someone dressed in an ill-fitting tuxedo. He was loyal and erratic, and loved to kill rodents and rabbits. He would eat his quarry on the spot, frequently in one or two gulps, bones, fur and all. We suspected he was part Plott hound, and more than anything in the world he loved to run. So on our walks we would often make our way over to that country land off Stanhope, and once on the other side of the guardrail, I would unclip the tether from his collar and he would dart off like a greyhound. One early summer evening Forest began frantically circling a willow oak that grew up on a sort of hammock of rich soil. In among its massive roots there were a number of holes dug deep into the red clay, and in an instant Forest dove snout first into it. His hindquarters tensed up and his barking became a deep and steady growl. And then there was single yip, and Forest backed out of the hole and cowered low to the ground, making his way over to me. There were streaks of blood from his forehead to his nose—three perfectly straight lines, one crossing his eyelids. At home, I washed the wounds with hydrogen peroxide and alcohol and then applied a few dabs of neosporin.

A week later we were back on Bellevue’s country lane, and Forest made a beeline back to the willow oak, but this time he went into a much larger hole on the other side of the tree. He barked, and growled. And then another sound rose out of the ground. It sounded like the chirping of a bird, but very loud, and there was a rapid whistling like a tea kettle. After five minutes, Forest backed out of the burrow. He dragged out the body of a large animal with brownish fur. It was fully two feet long and was the only groundhog I had ever seen in one of Bellevue’s alleys.