The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Yee Shun, and the View From Gold Mountain

by Jack R. Johnson 04.2021

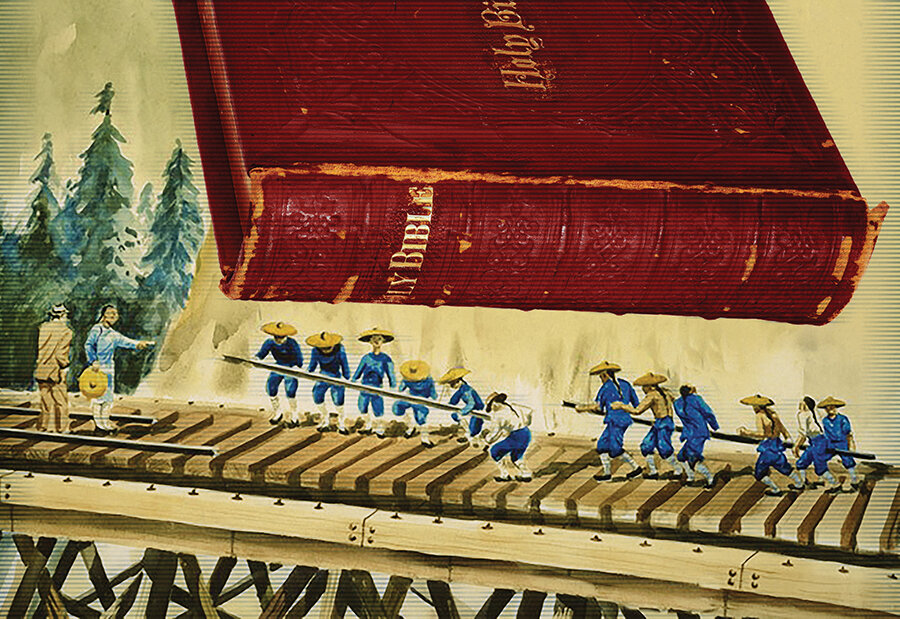

“Gold Mountain!” That was name the Chinese laborers used for the American West during the Gold Rush when thousands of their countrymen streamed into the country, looking, of course, for gold, but also for work, which was in ample supply. In fact, most Asian immigrants never got rich from gold. Instead, after arriving on these shores, they worked as itinerant farm laborers and factory hands, cooked food, pressed shirts, and laid railroad tracks. Lots of them. Their labor helped to build one of the more magnificent accomplishments of 19th century American engineering—the transcontinental railroad system.

But the Chinese labor force was not welcomed by many white Americans, who felt threatened by workers who spoke a different language, practiced a different religion and were willing to work dangerous rail laying jobs for much less money. Labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor and Knights of Labor found them threatening and favored passing laws to prevent their immigration (The only American labor union that supported their right to work in the U.S. at that time was the Industrial Workers of the World).

The politicians of the day listened. By the 1880s, anti-Chinese sentiment reached its peak with the Chinese Exclusion Acts, a series of laws that restricted immigration from China and limited Chinese-born people’s civil rights within the U.S. They were draconian to say the least—akin to laws used against Blacks in the same era. They suspended immigration for ten years, required Chinese people to carry documentation at all times, and refused Chinese people the ability to become naturalized citizens. They were not allowed to vote, and were not even allowed to testify in court because they were not “Christian”, and thus could not be sworn in. Consider: if you were Chinese in America after 1882, you could not even legally defend yourself in court if you were cheated in business dealings—a quite common occurrence.

But a little-known case, Territory of New Mexico v. Yee Shun would change some of that. The case was about a disputed murder charge, a murder that occurred on the evening of February 24, 1882 when a 20-year old newly arrived Chinese immigrant, Yee Shun, stepped off a train platform in East Las Vegas, New Mexico. He was on his way to Albuquerque in search of a job, but, unfortunately, decided to make a stop in East Las Vegas to check in with a friend, Gum Fing. When Yee Shun walked into the local Chinese laundry to inquire the whereabouts of Fing, someone fired a shot. Shun ran out of the laundry. Inside, a man named Jim Lee (who was also known as Sam Ling King or Frank) had been murdered. A group of white New Mexicans saw him running and tackled him to the ground. Yee Shun was dragged to the local sheriff’s office and arrested for the murder which he vehemently denied.

At the trial, Jo Chinaman, the laundry’s owner, was called to testify. When he faced the judge, he was asked about whether he was Christian and whether he understood the court’s oath. Jo Chinaman said that he was not a Christian and didn’t understand the oath, but that he would tell the truth. Then he testified that Yee had killed Jim Lee.

According to Erin Blakemore, Yee was found guilty of second-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison. Following an unsuccessful appeal, a despairing Yee committed suicide by hanging himself with knotted together bed linens.

Yee Shun’s life was tragic, but his legal case turned into a small victory for the rights of fellow Asian-Americans. During his lawyer’s failed appeal, he claimed that Jo Chinaman’s testimony was invalid because he was "of the Chinese religion,” and so his oath could not hold up in court. But New Mexico’s territorial Supreme Court judge disagreed. He upheld the conviction, and in the process established the precedent that Asian-Americans had the right to testify in court.

“Prior to Yee Shun, the legal right of Chinese to testify in court was unclear,” writes historian John R. Wunder. “The stumbling block was the oath.” The appellate court’s acceptance of Jo Chinaman’s testimony in court set a precedent that opened up the door for Chinese people to testify.

This hardly eradicated the anti-Asian sentiment that has flared up periodically in America culture. The Chinese Exclusion Act was extended for another 10 years in 1892, but it was eventually repealed by the 1943 Magnuson Act when China had become an ally of the U.S. against Japan in World War II. Later, on June 18, 2012, the United States House of Representatives passed H.Res. 683, a resolution introduced by Congresswoman Judy Chu that formally expressed the regret of the House of Representatives for the Chinese Exclusion Act.

And, finally, just last year, Yee Shun’s landmark legal case has been memorialized with a public monument in New Mexico. Created by Seattle artists Cheryll Leo-Gwin and Stewart Wong, it was installed outside the Bernalillo County Courthouse in Albuquerque, N.M. on Jan. 11, 2020.

Its title is “View from Gold Mountain.”

https://nwasianweekly.com/2020/01/view-from-gold-mountain/