Dawn Flores: Out of Many One

by Charles McGuigan 11.2025

On display at International Arts & Artists at Hillyer, Washington DC, May 2025

Each memory, every experience. A smell, a taste. Words overheard, or spoken. Moss under bare feet. Melodies that prick up the ears. A brief view of a forest path. The rise of a bullfrog moon over open water. Small things that embody a fleeting moment—good or bad. These elements unto themselves might seem like just so many scraps of cloth. But when stitched together by patient hands, guided by an artistic heart, they can become the quilt of an entire lifetime.

Dawn Flores works a sort of magic with her art, illuminating some of the darkest corners of our cultural consciousness and revealing truths many do not want to accept. It’s a complex process but the results are well worth the effort. This past spring three of her long-term art projects were on display for an entire month in the gallery at International Art and Artists at Hillyer in Washington, D.C. just around the corner from The Phillips Collection. Among those three works was The Atonement Flag. After the exhibit came down and the Flag returned to Richmond, Dawn performed a cleansing ritual on Juneteenth along the Slave Trail. At the Hillyer exhibit she had placed a basket next to the Flag and invited viewers to write messages of atonement on slips of dissolving paper. She carried those messages with her to the Slave Trail and read each one of them aloud and then scattered them in the James River where they were instantly swallowed up becoming one with the waters.

By the time she was just six years old, Dawn knew what she would be doing for the rest of her life. It started with a fire in the family barn.

When she was five, voices in the darkness woke her. She recognized one of them; it was her mom. Dawn’s eyes opened wide and she was instantly petrified. A large man, dressed like no man she had ever seen before and wearing a strange sort of helmet, was bent over her with his arms outstretched as if he were going to grab her. She then noticed her mother off to the side of this man.

“The barn's on fire and your dad’s trying to get the horse out,” her mom said. “I’m gonna get your sisters, so you just go with this fireman.” Out in the front yard, Dawn looked at the glowing faces of the firemen and the neighbors who had gathered. It all seemed like a dream and for many months afterward she would have nightmares of her entire family being engulfed by flames, burnt alive. So she would pray long and hard before she drifted off to sleep, and ended up making a compact with God. She promised the Author of All Things that she would become a nurse and devote her life to helping others, if the Creator would guarantee that nothing bad would ever happen to her family.

Not long after she turned six, Dawn renegotiated her contract with God. The family was at a drive-in theater, and the three sisters sat in the back seat watching the first feature, a blood-curdling horror film with Vincent Price called “Cry of the Banshee.” This film deepened Dawn’s trauma. But then the second movie began, and the young girl was immediately drawn in. It was titled “The Agony and the Ecstasy” and was about Michelangelo. Dawn was impressed by the way this artist stood up to pope, so she made a decision then and there about what she would do with the rest of her life.

“I’m really sorry God,” she said with her inner voice. “I think You can find other people to become doctors and nurses, but I think I would be better suited to being an artist and that’s what I’m gonna do.”

And she has held true to her promise.

From an early age, Dawn possessed a creative drive, which her mother, who also had an artistic streak, always encouraged.

“I was painting in acrylics by the time I was eleven,” Dawn tells me. “And then I started doing pastels when I was seventeen, oil pastels and chalk pastels. I was also writing poetry, and I did a lot of performance in church.”

In high school she took art classes, and remembers one instructor who doubted her abilities.

“I’d take my work home and then I’d work on it over the weekend and I’d bring it back to school on the bus,” Dawn recalls.

As she was working on a painting in an acrylics class one day, her instructor stood over her, looking down on her progress, and then he said something that shook the young artist to her core.

“I know your mother's a painter and you're taking it home and having her paint it for you,” he said.

For a moment, Dawn was without words. But then she said this: “My mom's a painter, but she's not as good as me. And this is my painting.”

Not long after that, as Dawn and one of her friends were collecting their art supplies, another one of her art teachers, a man named John Deering, approached her.

“Congratulations, Dawn,” he said.

“For what?” said Dawn.

“Your painting won first place at state.” he said.

“I didn't even know it was entered.”

“I entered it for you,” Mr. Deering told her. “And you won a scholarship to University of Wisconsin, at Green Bay, for summer art camp. You're supposed to go to the Nevil Public Museum tomorrow.”

The entry was a somewhat surreal painting of a man’s torso opened up and the internal organs exposed. The blood vessels and arteries were pipes, the intestines a snake. She was a high school sophomore at the time and just one of seven recipients of the award. The six other winners were all seniors and they were males. A write up on Dawn appeared in the Pulaski News and the Green Bay Press Gazette.

“And I became instantly legitimate,” Dawn remembers. “I wasn’t the weirdo anymore. I was the celebrity.”

Along with being a visual artist, Dawn was also a writer and an actress and a musician.

After high school she attended Edgewood College, a small Catholic school in Madison, Wisconsin where she studied both art and theatre, excelling at both. She played the lead in Jean Anouilh’s version of Antigone. In theatre lab she set music by Blondie to a poem by Erica Jong. “And then I set it up for another woman to play Sylvia Plath and she reads an essay about belonging to a sorority,” says Dawn.

Her schedule with a dual major was extremely demanding. “I was trying to do both equally well, and then theatre was demanding more and more of my time.” So she decided to drop her art major, which she mentioned to Sister Stephanie Stauder, a guidance counselor.

“Meet me under the holly tree on the concrete bench at four o’clock,” Sister Stephanie told her.

Mason Dixon Forest, 2020,6'x8'

Dawn was seated on the bench at the appointed time, and Sister Stephanie approached her, but instead of sitting next to, stood by her side.

She looked Dawn in the eyes and then said: “You were born a painter and you will be a painter till the day you die.”

Dawn broke down in tears and decided to keep the art major, but she would end up leaving Edgewood at the end of her junior year and enrolled at University of Wisconsin Madison the following year. There she took classes in art and art history, and in feminist theory and dance. And because of the setup of the house she was renting with other students, Dawn had the entire second floor to herself. “I started making art like crazy,” she says. “I put my drawing table in one corner of my room, and my easel in another, and my sewing machine in another. And my writing desk in another corner.”

Over Christmas vacation, while the other members of her household were home for the holidays, she decided to live a full month without distractions. “I wanted to elongate my attention span so I would start in the morning dancing, and then I would draw as long as I wanted to, and then I would paint as long as I wanted to, and then I would read as long as I wanted to. I did it for a whole solid month without talking on the telephone.” She left school the following semester and began applying herself to art. She worked in pastels, watercolor and acrylics, and found a job that would allow her ample time for her art.

Dawn would later live in New Orleans and New York, always pursuing her art—writing, performing or painting. Throughout it all she would work an assortment of jobs, whether it was waiting tables or creating windows for Barneys.

She would later move to Richmond with her former husband and join the Women’s Caucus for Art. She continued writing, performing and showing her work at a number of area galleries, while holding down full-time jobs.

Some years back, while raising her two children and living in a home that abutted a massive wooded area—part of the Bliley family farm—three things happened on about the same time that would send Dawn down a new path with her art. Her mother passed away after a long bout with ovarian cancer. Add to that, Dawn was re-evaluating her marriage. And then the bulldozers and chainsaws came as developers cleared the land that bordered her property.

“Everything was crumbling,” she says. “It was a good time to have a nervous breakdown. Or a breakthrough. I never had a breakdown, but I did have a dark night of the soul. I had a lot of grief on my plate. My muse was the forest and it was being cut down. I knew I had tools and I knew I had to activate those tools.”

That was the birth of The Forest Project, which she would work on tirelessly for a full eight years. Dawn mobilized her neighborhood and worked with the developer who permitted her to document the harvesting of trees, even offered to let her have some of the felled trees.

“So I started contacting everybody I could think of to come out there and we rescued two thousand plants and collected a million seeds,” Dawn says. “I worked with Richmond Woodturners. We cut down sixteen species of trees and distributed the wood to fifty members of the group and they came back with bowls and platters. I started taking photographs of the woods and turning them into fabric patterns, and printing them on fabric and then making them into quilts. And when they cut the trees I would drape the quilts over the trees and when they were cut down I would lay the quilts on the bare earth as a thank you for what was.”

When Covid struck back in 2020, Dawn suddenly had all the time in the world to create. “I was like, ‘I can do anything I want,’” she says. “That’s when I started working on two projects—Plantation Hands and Mason Dixon Forest.”

On the property behind her house and in the basement of the old home site there she found scores of old bottles, among them Mason jars and Dixie wine bottles. She had also found an old cabinet that had been in the house.

“So I decided to put all the seeds, the soil, and some water from the forest that no longer exists in bottles,” says Dawn. “All one hundred and sixty bottles were sealed. Seeds. Soil. Water. But they lacked union so they couldn’t germinate, grow fruit, or nourish. And I backlit it all so it glowed like a sarcophagus.”

The other project she worked on during that period was inspired by a civil rights tour of the South she went on with her current husband, Jack R Johnson. “Whenever we were going to these museums and historic sites I was looking at what the white women were doing to support white supremacy,” Dawn recalls. “That’s what I wanted my piece to be about. They’re not these innocent bystanders. They were active participants in upholding the institution of slavery.”

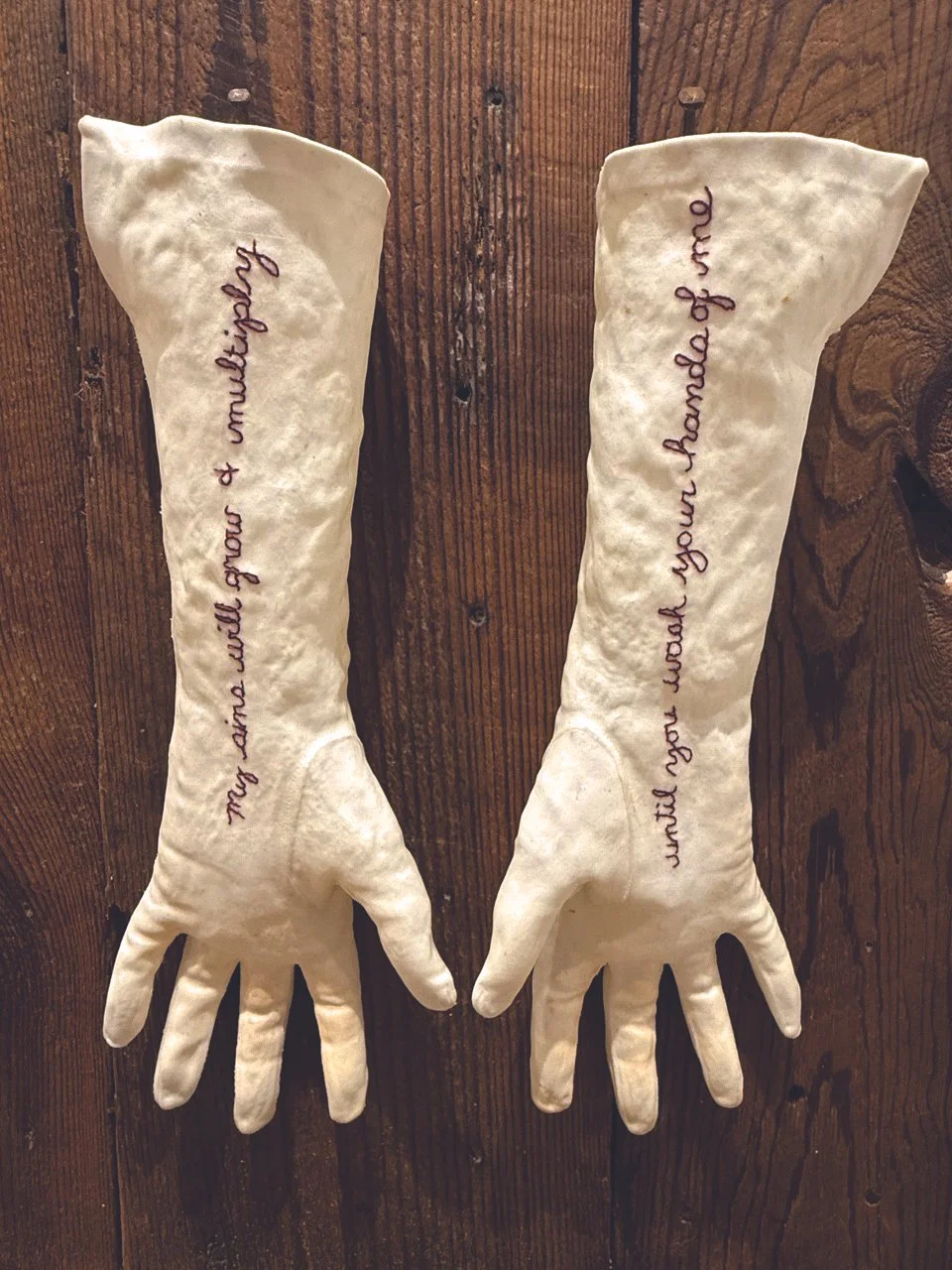

Close up Plantation Hands

So she found ten pairs of cotillion gloves and embroidered each one in red thread with a single line of a poem she had written. These are the words Dawn penned:

“I use gossip, lies and innuendo, to bolster my sense of superiority.

I leverage the rule of law, to enslave and commodify.

I twist the word of God, to justify my inhumanity.

Born into a system, I survive through self-preservation.

I maintain control through terror, brutal violence and threats.

Trained from birth, in moral cruelty…

I line my pocket with heartbreak, wrought from family separation.

I steal my sister’s body, and everything issued from it.

My world is neither benevolent nor kindly, but I will campaign as if it were.

My sins will grow and multiply, until you wash your hands of me.”

And each glove hung from a single nail driven into rough hewn boards. “I wanted it to look like a wanted poster,” Dawn says. “And it’s all made from salvaged materials.”

At about the same time the country was finally emerging from the Covid lockdowns, George Floyd was brutally murdered by a policeman.

As the Black Lives Matter protests kicked into full gear and calls for the removal of Confederate statues along Monument Avenue reached a crescendo, Dawn was there.

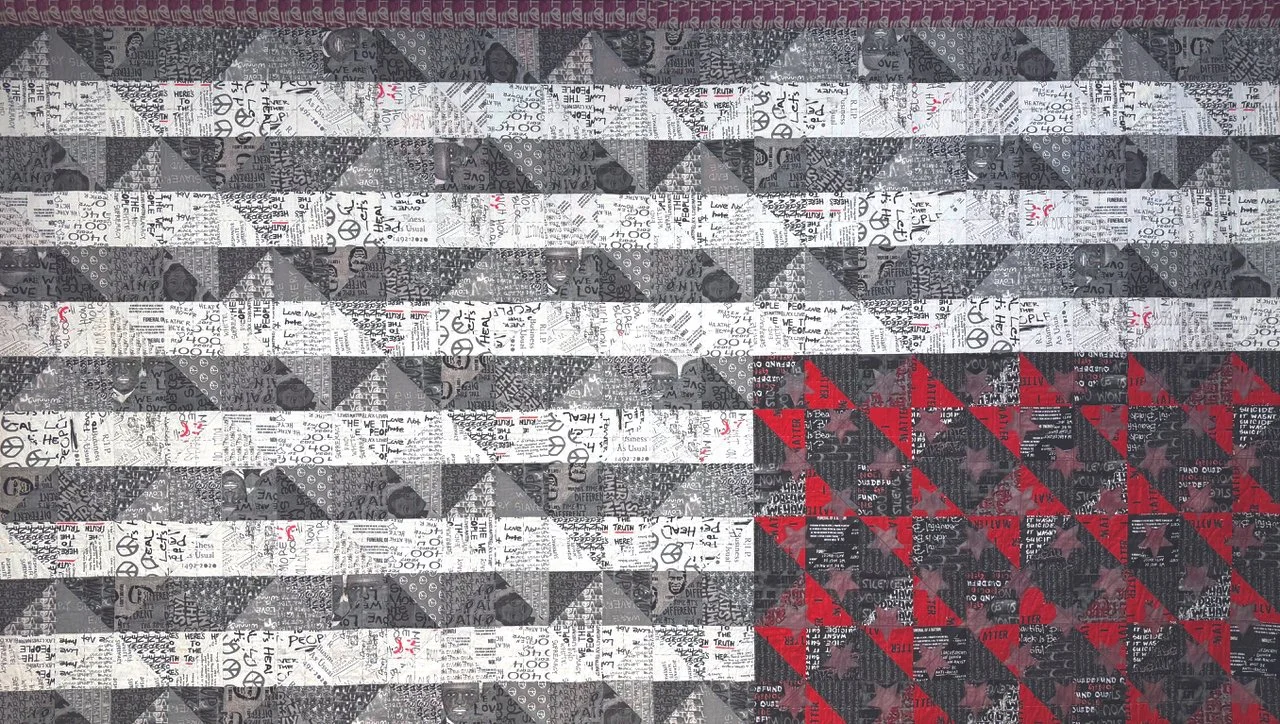

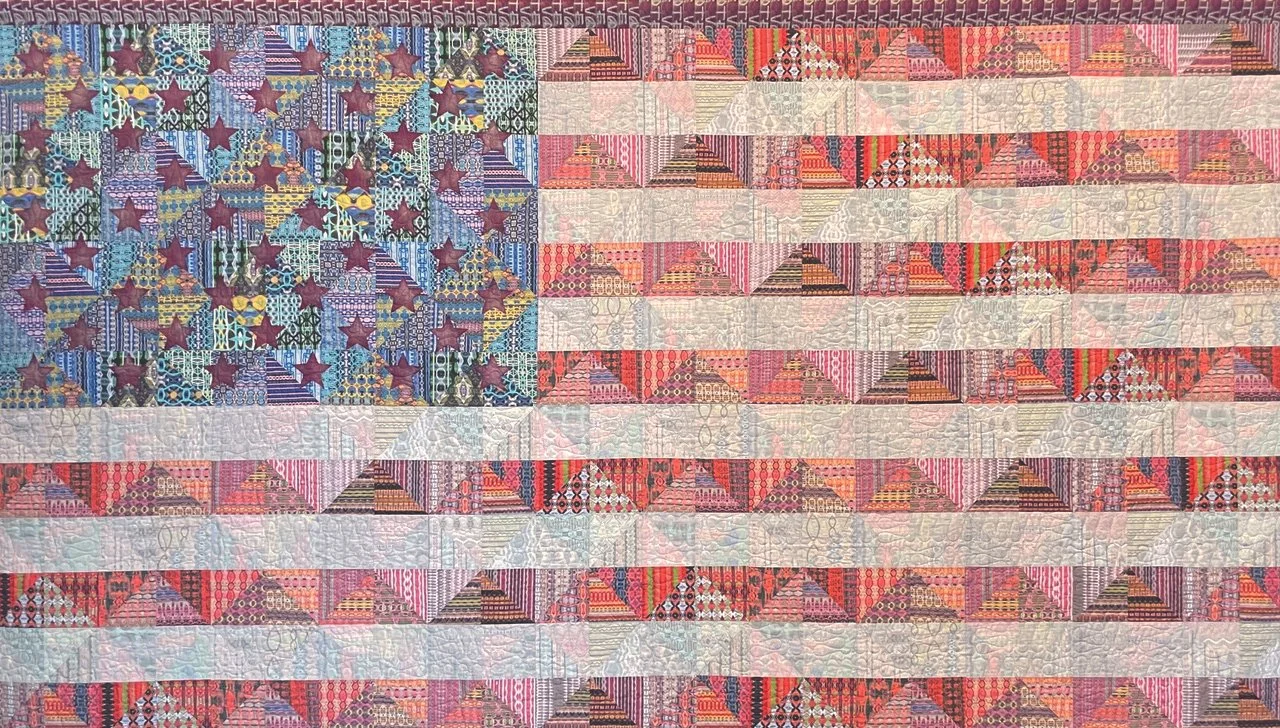

“All hell breaks loose.” she remembers. “I go down to see it. I see the graffiti at the base of the monuments and I see a green squiggly line on the United Daughters of the Confederacy. I thought, I can make a fabric pattern out of the graffiti. Then my brain exploded: I can make a quilt.”

That’s when she envisioned The Atonement Flag. And it would be like no other American flag in existence. It would have two sides. “One side would be right side up denoting our perfect union,” says Dawn. “The other side would be upside down denoting the sins of our foundation in white supremacy.”

She would take hundreds, if not thousands, of photographs of the elaborate graffiti that adorned the bases of the monuments during the protests. She would work with the images in Photoshop and then transfer them to fabric, which she would cut into pieces and then hand-stitch them together and create this massive quilt that would measure a full six feet wide and twelve feet long.

Atonement Flag back 6'x12'

Atonement Flag front 6'x12'

The Atonement Flag was first exhibited at the Unity of Richmond Church. Next it was shown in collaboration with Race in Richmond at Main Street Station. Dawn then took it out to Wisconsin where she unveiled it on her father’s farm the same day the current administration ordered federal troops into the nation’s capital. And, of course, last spring it had been part of Dawn’s exhibit at International Art and Artists at Hillyer in Washington. Earlier this month it was displayed at the 55th Anniversary of The People’s Flag Show at Judson Commons across the street from Washington Square Park in New York City.

“A lot of my art is about grief,” Dawn Flores says. “I use the rituals of grief to process moments of great change in our culture, personal to me, and political to our nation.”

This quilted flag is the kind of gut punch all great art is. Like Picasso’s Guernica, like Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais, Dawn’s The Atonement Flag will not permit you to turn your head and cast your eyes elsewhere to avoid undeniable truth, and rewrite history. You will, if human, feel an overwhelming sadness, and a deep desire to put right what is wrong.