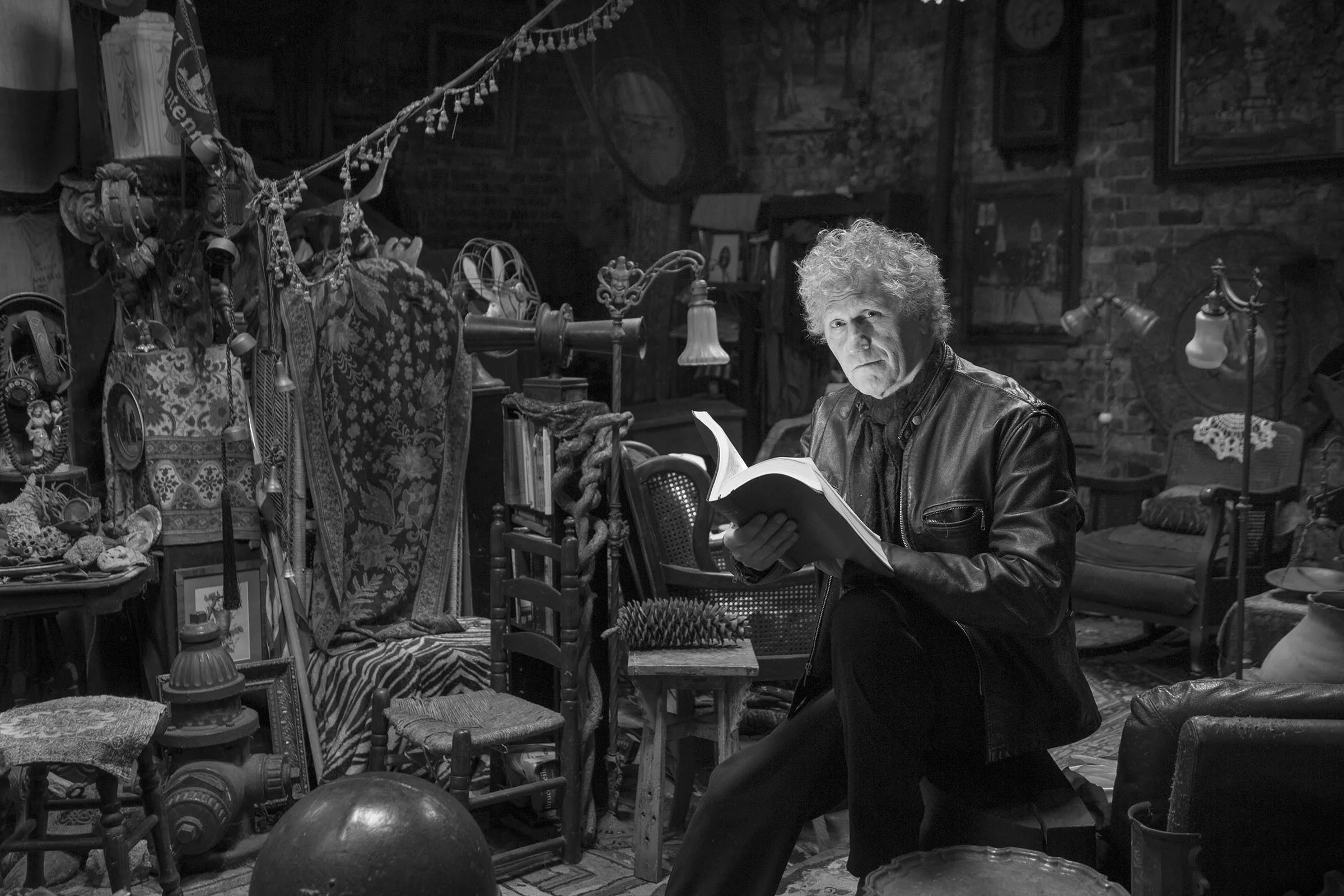

Self portrait by John Henley

John Henley: The Picture Maker

by Charles McGuigan 02.2026

Art photography does not “capture” an image, trapping it like an animal, snared and then dumped into a cage. Something I did not know before I spoke with John Henley. It’s not that at all. The art of photography may freeze a specific moment in time, but there’s much more to it than that. For the eyes of the artist who practices in this medium have direct lines to both the heart and the mind. Perhaps even the soul. And after a thousand clicks, and over a dozen return trips to the same spot, that ideal image just might be recorded. It is a marvel that is transformative. And then the work continues in the darkroom—the sacrarium of the photographer.

When John Henley was a child of three, living with his parents in an apartment on West Franklin Street just east of Stuart Circle, something grabbed his full attention, had him mesmerized, and he was forever on the lookout for its recurrence. He would watch a truck drop their chutes through a basement window into a coal bin, and then a rumbling screech like a low rolling thunder would last until the final black nugget bounced down the steel slide into the mouth of a cellar.

The Henleys then migrated west, settling in Glen Burnie where John attended school at Westhampton. On his way to school in the morning at about 8:30, he and a couple of friends would stop at Joe’s Seafood on Patterson Avenue and buy Coca-Colas from the vending machine out front. And they would peer through the storefront glass and watch as old men drank their beer at the bar. It was one of many images that stayed with John.

After finishing eighth grade at Westhampton he went through high school at Thomas Jefferson, but had absolutely no idea about what he wanted to become. This was in 1965, and the Army scooped him up, but instead of sending him off to Vietnam he was assigned to a tank unit in a village just outside of Nuremberg, Germany. And that’s when he began to take a shine to photography.

“In the PX I bought a Pentax 35 millimeter camera and at the time that was the next best thing to a Nikon,” John tells me. “I took bad pictures of Europe. But I kind of got the bug.”

Richard Bland, by John Henley

After a two-year stint, John returned stateside. “And when I came back my parents were so happy that I was interested in anything at all that they offered to send me to art school to pursue photography,” says John. “So I went to this place called the San Francisco Art Institute which was a really well-known art school.”

During John’s time at the art institute, his voice began to emerge. “It was an extraordinary school and I got a BFA,” he says. “I learned how to take pictures and I developed a style in my photography. I used high speed film and I pushed it up even higher to get this grainy look that I liked. And I overdeveloped the film to get the highlights to be blown out a little bit. I wanted it to a have a slightly dreamy quality and my aesthetic has not changed drastically. I’m basically a romantic at heart.”

When he came back east to Richmond, John was doing a fair amount of what he calls his “personal work.” But he needed to make a living, so he started hitting up some of the local ad agencies.

“Some young art directors at the Martin Agency were working on a pro bono project and they said, ‘We want to do some sort of artsy thing,’” John remembers. “So they hired me to do it because they wanted an artsy edge to it. And they liked it and then they hired me again and things started happening. I was somewhat reluctant in a way. But people started hiring me and I needed the money.”

Along with Martin he also did work for Burford Advertising and other agencies in Richmond, but he was also getting work outside of Virginia.

“I started getting hired all over the country,” says John. “One of my favorite ones was for Santa Fe tourism. My idea was to have a guy painting the sky with a roller and it ended up winning some big awards.”

He tells me how he shot it—the old school way before CGI and other software shortcuts. “I found this ranch out there where they filmed ‘Lonesome Dove,’” he says. “It was a beautiful place and we went out there three or four days until I got a great sky. We didn’t have a model because I couldn’t afford it.” So instead, he used the copywriter. He had him climb to the top of a tall stepladder and with a roller at the end of an extension pole pretend to be painting the sky.

Pumphouse, by John Henley

“I didn’t get the clouds I wanted until the last day and these beautiful golden clouds came in and it looked like he was painting the sky with a roller,” John says. “That was the coolest ad I ever did. That’s one of the few I like enough. I don’t call it art because it was advertising, but it was something I was very proud of.”

Throughout his career in advertising, John always made time for his artistic photography. “I’ve had a number of shows in Richmond and I won a VMFA fellowship,” he says. He also went back to school and earned a master of fine arts in photography so he could teach.

“I taught at VCU between 1990 and 2005 for almost every semester,” he says. John also taught photography at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College and Virginia State University.

And over the years he has produced a number of books. In the past five years alone he created three, and is currently working on yet another.

Along with one he did on the Virginia War Memorial, John also put together one titled “ARTISTS” and another called “The Kanawha Canal Photographs.” Both volumes are composed of only black-and-white photos, and each shot, whether portrait or landscape, attests to the singular talent of the man behind the lens, this wizard of the visual arts.

“ARTISTS” is a veritable Who’s Who of Richmond artists, and each of the one hundred portraits within perfectly reflects its subject. None of it is overly stylized.

“When I did that book of portraits I really had to struggle,” John says. “A lot of times I was able to work with them, and talk with them, and I had them already framed, so I wasn’t looking through the camera. I might only get one or two pictures out of a hundred I shot, but I love portrait photography.”

And his love for certain places can be equally strong. “My photography is kind of a mirror of where I am at any given time and it’s the way I look at the world, the way I see the world, what’s interesting me at that particular time,” says John. “A good example would be the Kanawha Canal.”

Kanawha Canal, by John Henley

When he was down at the Great Shiplock Park one day, the weather snagged his artist’s brain. “I saw those buildings sort of shrouded in the mist in the background and I just thought, this is what this looked like before those buildings were there,” he says. “So the buildings just sort of magically appeared behind the mist and that was the whole idea for it. That picture to me, what was fascinating to me was that city, even if they didn’t celebrate it, at least they didn’t paper it over. This is a fascinating part of the city that nobody pays much attention to and I have to bring people’s attention to this. So I decided I’m going to go down this canal everywhere I can get a picture of it.

John’s photographs of the Kanawha Canal hang on the walls of The Valentine. “I loved doing that project because I knew when I was doing it that it was good.” he says. “I shot all of those with a Toyo four by five field camera. I think that my main two loves are landscapes and portraits.”

He then tells me a bit about the difference between painters and photographers. “It’s such a different way of looking at the world because photography literally is looking at the world,” he says. “And so I don’t think very many painters go around like I do, constantly seeing images that I would like to make. And that’s the way good photographers mostly are. They are seeing photos. Even when you’re not taking pictures you’re looking.”

John points out the window next to him and invites me to look outside at the side street. “Isn’t that telephone pole there interesting?” he says. “The way it divides the fence and the house and how would that mess with people’s sense of space? That’s the way photographers see the world. They are always looking.”

As of late, John’s vision has been trained on a distinctive county to Richmond’s east. He calls it The Charles City Project. Not long ago an old and dear friend of his who lived there passed away. “Jack Christian lived in an old farmhouse,” John says. “But also I became interested in Charles City County because it’s uniquely different than any other county around here. It is unto itself. There are no malls. There are no chain stores there and only a few very wealthy people live there.”

He’s taken photographs of a dirt road lined on both sides by Virginia cedars and a silo covered with kudzu as if the earth were reclaiming it. “The one of the silo is almost surreal looking,” he says. “When I was photographing an old gas station an old truck was pulling out and it throws out this huge plume of smoke .. .”

“And you captured that?” I suggest.

He nods. “I got the picture,” he says. “I don’t like that term. Captured. It’s something that art photographers don’t say very often. The trouble with captured is that it’s like you trapped something. But there’s so much more to making a photo like that.”

John Henley leans back. “First of all it’s seeing it, and it’s framing the picture right, using all the right things that make that picture work. But it’s not capturing or grabbing something. When you make an image, you’ve transformed something from a moment in time. And then you go into the darkroom and make this image. It’s a transformational process, and capture does not describe it. I am a picture maker.”