Meghan Varner a Silver Lining

by Charles McGuigan 04.2023

Photos by Rebecca D’Angelo

Meghan Varner grew up on a tree-lined street in a neighborhood filled with Arts and Crafts cottages. In her backyard, twenty feet off the ground, was the best treehouse in all of Bellevue. It was painted green and had electricity but no plumbing, and Meghan played in this lofty fortress for hours on end, thinking of the things she would one day do. She could already do what many of her peers couldn’t. For instance, she could bring her feet over her head while sitting down. And she could do splits without any effort at all. This, too: Meghan seemed to be double-jointed, or that’s what people called it. Her parents had begun to notice some of these traits in their only daughter when the girl was just two years old. As she grew older Meghan could bend her fingers backward as well as forward, as if none of her joints had a one-way hinge. Her parents were told by doctors that Meghan would grow out of it. But she never did.

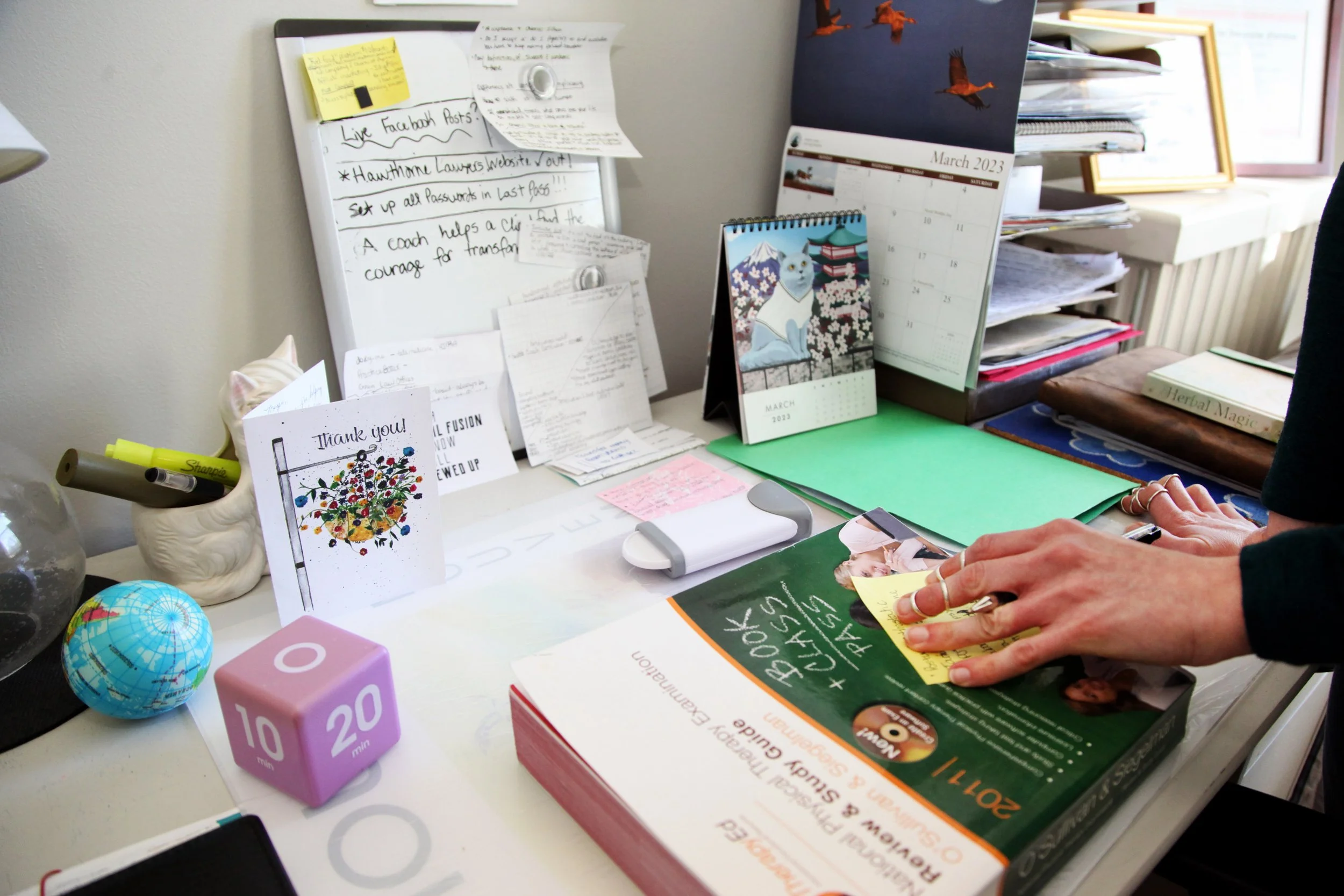

Meghan Varner sits across from me, her hands palm down, flattened on the table top. Around virtually every finger joint there are these very exotic looking silver rings, almost like a series of coils that wrap around each segment of every finger.

“These beautiful rings on my fingers are for where my joints partially dislocate,” Meghan tells me. “That dislocation is called subluxation.” And the rings are actually splints that help limit the movement of her finger joints which are hypermobile symptomatic of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), one of the two disorders Meghan has.

While attending Luther Memorial School (long since closed), Meghan had her very first encounters with physical therapists at Children’s Hospital, which was then located on the massive lot right next to the school's campus. “I would walk over there from school,” she says.

Her days at Luther were not the best. Meghan had to wear leg braces which acted pretty much like the ring splints she now wears. “I was a good target for some bullying there,” she recalls.

So when she was in sixth grade her parents enrolled her in Landmark Christian on Creighton Road. Though somewhat restricted by EDS, Meghan was physically very active. “I did basketball,” she says. “I did horseback riding on the side, that’s another love of mine. I even had my own horse at one point.”

But there was a spinal deformity that needed immediate attention by the time Meghan entered her junior year in high school. She had major back surgery that lasted a full eight hours. Surgeons had fused part of her spinal column and there would be a long recovery period. “Recovering from back surgery is difficult,” says Meghan. “You’re lying down a certain portion of the day, and then you’re upright. You are rearranging your spine.”

During that recovery period, Meghan persevered in her academic pursuits with the aid of tutors, and then she and her parents made a decision for her senior year. “I started in a home school program where you go two days a week and then do your assignments on your own,” she says. “It was amazing. It prepared me for college.”

There would be subsequent surgeries, and after each one Meghan would spend a lot of time with physical therapists. “So where do you think I got my interest and my passion for physical therapy?” Meghan asks. “I loved science as a kid. I was interested in the way the human body works, and I wanted to do something in some way where I could serve people.”

So while still an undergraduate at Randolph Macon College in Ashland where she majored in biology with a minor in chemistry, Meghan decided to become a physical therapist. After earning her bachelor’s at Randolph Macon, she began a clinical doctorate program at Virginia Commonwealth University. “They have a great program,” Meghan says. “So I stayed in the neighborhood, saved money, and lived at home for the three years of graduate school.”

While still attending VCU, Meghan had a second back surgery. “It was a revision of the first one,” she says. “I asked myself, ‘Why is this happening to me? This isn’t fair.’ I had it done over a break because I’m a Type A personality, very driven, so didn’t take a year off.”

With seven years of college under her belt, Meghan got her first job as a physical therapist in Fredericksburg at an outpatient orthopedic manual therapy clinic. “I loved it,” says Meghan. “But my body kept falling apart.”

And neither Meghan nor the scores of doctors she had seen over the years were able to diagnose what was going on with her body. “I felt there has to be an underlying issue connecting all of this, and stress made it worse,” she says. “Somehow all of this had to be interconnected.”

Meghan’s health continued to decline while she was up in Fredericksburg.

“My fatigue was getting worse, and there was brain fog and extreme exhaustion,” she remembers. “I would go to sleep and couldn’t recover. My glands in my neck started to swell, I had low grade fevers and chills, weird body aches and muscle spasms. I would try to sleep at night, but I just couldn’t fall asleep. It was that tired but wired feeling. You kind of feel like you’re outside your body.”

She saw specialist after specialist, and none of them could diagnose what was ailing Meghan. So Meghan decided to leave her job. “I thought it must be the stress of my job,” she says. “Pushing and pulling on people, popping my joints in and out. I needed to do something less physically demanding.”

That’s when she began course work for a PhD in rehab and movement science at VCU. “I thought I would be able to do research or be a professor, something less physically demanding,” says Meghan.

And then one day, as she was headed home from VCU’s health science campus in downtown Richmond, Meghan nearly passed out at the wheel. What’s more, she couldn’t remember how to get back to her home in Bellevue along a route she had driven many times before. “My memory was gone,” she says. “It was scary. I was having trouble walking up and down the hills.”

After much consideration, Meghan opted to leave the PhD program and seek in earnest what was going on with her. “I took time off and kept searching, and tried a different endocrinologist,” she says.

This endocrinologist, a woman, asked all the right questions, and listened carefully to Meghan. After hearing Meghan’s long list of symptoms, she asked her this:“Have you ever heard of POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome)?

“No,” Meghan replied. “What is that?”

She would learn a lot about this syndrome which had plagued her since childhood. POTS is a form of dysautonomia, a disorder of the autonomic nervous system which regulates functions we don’t consciously control, such as heart rate, blood pressure, sweating and body temperature, and it can be difficult to diagnose. “It’s pretty common with POTS to take that long to get diagnosed,” says Meghan. “It can take up to ten years to diagnose. The POTS diagnosis gave relief. But now what? How am I going to manage this?”

There was a long road ahead, along with another diagnosis, this one for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), an inherited disorder which affects connective tissues. Folks with EDS have extremely flexible joints. “So when you think of someone being extremely flexible or hypermobile you think of circus performers,” says Meghan. “That’s like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.”

That same summer, back in 2015, Meghan would undergo a few gastro-intestinal surgeries. “That set me back,” she says. “I figured out how to manage it. It was finding a doctor and a cocktail that worked for me. Finding a form of exercise so I could gradually build myself up, and rebuild my upright tolerance.” The meds she took in the cocktail included beta blockers and anti-spasmodics. “And the first line of treatment with POTS is fluid loading,” Meghan tells me. “Increasing your fluid intake along with sodium and other electrolytes. I also began wearing compression stockings to get that blood back up to my brain.”

She began working again as a physical therapist in 2017, and two years later married Ray Varner, the man she first met during her Randolph Macon days.

By 2020, Meghan was working as a physical therapist for a health agency called Heaven Sent. “They were one of the better ones,” she says. “They really valued patient care; and it wasn’t focused on quantity, it was focused on quality.”

The routine with home health care suited her. “You see patients during the day, you come home and do your notes, you arrange your schedule for the next day,” says Meghan. “I did really enjoy collaborating and working with all of my colleagues. It’s not just PTs, it’s occupational therapists, nurses, and social workers.”

While working at Heaven Sent a sort of seed was planted in Meghan’s mind. “We were there to help clients keep up with whatever things we were trying to educate them on with diet and exercise,” she says. “We were teaching them what to do on a routine basis so that they wouldn’t find themselves back in the need of care. That piece contributed quite a bit to what began to get me thinking about something else I could do with my career.”

The rigors of the job were already taking their toll. Meghan was again exhausted. In February, to celebrate their anniversary, she and her husband took a trip out to Arizona, visited family and the Grand Canyon. But when she and Ray returned, Meghan was more exhausted than ever. “I knew the symptoms of going into a flare with POTS, and I was heading in that direction,” she says. “So we came back in March, and in April the world changed.” That’s when Covid shut it all down.

As bad as it was for the rest of us, it was ten times worse for the many healthcare workers on the front line. “It was a lot of uncertainty,” Meghan says. “It was a lot of stress levels of not knowing what the virus would do. The company I was working for didn’t know how many masks we had. You had to treat them like gold. There was a lot of stress.” And stress is one of the key triggers for flares of POTS.

“I called that stress the cherry on top of my sundae of demise,” says Meghan. “It got to me, and sent my nervous system into a state of fight, flight, or freeze.”

She would have to make a decision to keep working or quit her job. Fortunately for Meghan a cardiologist essentially made the decision for her. “I’m very grateful to the doctor I was seeing at the time,” she says. “He said, ‘You need to step back. Step back and let’s see what happens over the next few months. We don’t know what this virus will do to POTS. You could get very, very sick.” No one, not even epidemiologists, knew a damned thing about this novel virus.

“People were already dying, already having severe repercussions from it,” Meghan remembers. “We didn’t even know about long Covid then. Fast forward to now, individuals with long Covid are now being diagnosed with POTS and dysautonomia.” Prior to the pandemic, there were an estimated one to three million Americans with POTS. Experts now believe there may be an additional one million new POTS patients likely as a result of COVID-19.

Meaghan, at the very end of April, took the advice of her cardiologist and stopped working as a physical therapist. “It was a very tough decision,” she says. “To step back and say I have to let go of this was tough, and to watch other coworkers continue in it and to watch other friends in the healthcare profession continue in it, it was tough.”

Like the rest of us with any sense in those early days of the pandemic, Meaghan retreated to her home. “I was doing okay, doing yard work like we all were, or what we could do around our house to keep ourselves busy,” says Meaghan.

But Meaghan’s health issues got progressively worse. “I had trouble sleeping,” she says. “My GI issues got worse, my anxiety issues got worse.” And the heart in her chest raced every time she rose from bed, or stood up from a chair. It was POTS. “Normally your nervous system would communicate to your heart and bring your heart rate down,” Meaghan says. “But with POTS it can just keep going up.”

Despite all the adversity Meaghan experienced at that time, she discovered things about her disorder, and ways of combating the symptoms that would ultimately lead to a new profession, and a renewed purpose.

“This was the silver lining of the pandemic,” she says. “I took time off for a couple months. We were all stressed out about the pandemic. I was right there with everyone, and my nervous system was already primed to overreact and I was in a spiral of stress. I was very blessed to have a spouse who was able to support me. We were still doing okay, and I’m super grateful for that piece of the stress not being there.”

Instead of sleeping on the couch or binge-watching a Netflix series, Meaghan began searching for answers on-line. “I began to look into what can I do to come out of this,” she says. “And what can I do to still have purpose? To still be able to use what I know, my knowledge as a PT.”

She came across a blog called the Non-Clinical PT put together by another physical therapist, a woman who had battled cancer, and ultimately became a health coach.

“So I started exploring what that would look like for me,” says Meaghan. “I looked at going into a functional medicine-leaning, health-coaching training program, and that’s when I went to the Institute for Integrative Nutrition and completed their program.”

With her medical training, coupled with her own experience and her training as a health coach, Meghan launched Guide2Resilience. “I wanted to find something I could still do and do it from my house,” she says. “My business is one hundred percent virtual. I wanted a purpose. I have seven years of school, I have knowledge, I have this experience that has a meaning. And I have empathy for those that are suffering. How can I help these people so they don’t have to go through what I have gone through? ”

Meghan Varner then says this: “That silver lining of the pandemic gave me time, it smacked me in the face, and it said, ‘You need to listen to this and see how this is affecting you.’ And I’m getting there. I’m beginning to see that EDS and POTS are there as teachers, and they’re there as a weird blessing, as a weird gift.”