On the morning of March 24, Melvin Major, long-time owner of Fin & Feather Pet Center, passed away in his home on Dumbarton Avenue. He was a gracious man who, over the years, took hundreds of young men and young women under his protective wing. He is sorely missed by many. Although there was no viewing or funeral service, a celebration of his life will be held at a later date.

Melvin Major: Fathers And Children

by Charles McGuigan 2014

Aristotle said it best: “Nature abhors a vacuum.” Whenever there is a void in our lives we fill it, consciously or otherwise. Too often, people try to fill that hole with anything that’s available, things that can create a deeper hole, a hungry mouth that demands to be fed but regardless what and how much you feed it, it is never sated, for it is an abyss, a vast yawning gap, without end. But sometimes, if we’re lucky enough, the very thing that replaces the emptiness is what we needed all along and we can actually become the very person that was missing from our own life. Through that transformation we are then able to fill the voids in others and become truly human.

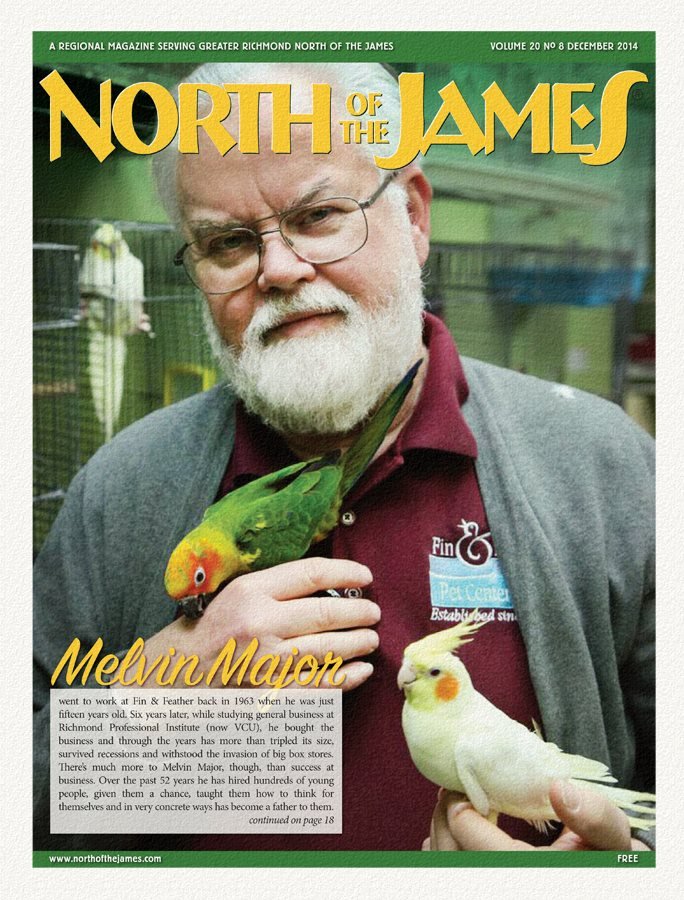

Melvin Major sits at his desk in the rear office at Fin & Feather, the last independently owned full-line pet store in the region where customer service is flawless, where all sales associates have deep knowledge of the products they sell, which are generally less expensive than they are at the big boxes or grocery stores.

Melvin’s beard and hair are white and his eyebrows form perfect arches like circumflex accents above his eyes. He is telling me about the Lakeside of his youth. There were three grocery stores, two full-service hardware stores, three pharmacies, two of which housed lunch counters, and an array of other shops and restaurants. It was a village unto its own, a sort of Mayberry—slow-paced, easy going, and everyone knew one another.

He grew up in his grandmother’s house where he still lives today, just nine-tenth of a mile from the front door of Fin & Feather. They kept chickens and ducks, guinea fowl and rabbits, and the back yard was filled with gardens. “We had it all,” says Melvin.

Melvin’s household was made up of his mother, grandmother, uncle, and, of course Melvin. But his father was not there. He had left his wife while she was pregnant and returned to his home in New Jersey. Melvin would not see this man until many years later. “I didn’t know my biological father until I turned eighteen,” he says. “I can’t really describe how it was. It was nice to meet him but it was no Eureka moment. I saw him four or five times after that and there was never really any bond.”

Just shy of his fifteenth birthday, Melvin applied for a part-time job at Fin & Feather. He was hired to work weekends and began learning the pet shop business. “It was the closest job I could find within walking distance from home,” he says.

He took to business like a swordtail to water. While still in high school he met a woman, a teacher named Mrs. Humphries, who taught graphic arts and mechanical drawing. “She was from a relatively well-off family and very well-educated,” he remembers. “And she would take a lot of the kids under her wing and take them to her house for dinner. She was one of the most memorable teachers I ever had.

She played a big role in my life.”

After high school graduation, still working part-time at the pet shop, Melvin began attending RPI (now VCU) where he studied general business. And then the former owner of Fin & Feather offered to sell the business and Melvin bought it. “It was only 2,000 square feet at the time,” he says. “We are now a little over 7,000 square feet. I have owned it for the past 45 years.”

In those intervening years, hundreds of young men and young women have worked at Fin & Feather where they found more than steady employment. They found a second home.

After Melvin purchased the property at 5200 Lakeside Avenue, which now houses the Pond Center, he began a ritual that lasted for about twenty years. “It was originally a house and the building was built onto the front of it as part of a business for the fellow who owned the house,” he says. “I used to cook breakfast for the employees there on Saturday and Sunday mornings. It was just part of a perk. I enjoyed cooking and fixing breakfast and giving the employees a chance to get together and just relax before they came to work. One year I cooked an entire Thanksgiving dinner for an employee and his friend that couldn’t get away to go home for Thanksgiving. I made soups and stews and barbeque, a big crockpot of stuff so they could eat on it during the day throughout the week.”

And in that same house, on the second floor, Melvin created an apartment with two-bedrooms and a bath. “I’ve let our employees who were college students and needed a place to stay live there,” he says. “To all my employees I’ve always expressed how important it is to get a good education and when they started school I would work around their college schedules.”

When I ask him why, he grins and uses words he might have heard from his high school teacher, Mrs. Humphries. “Because it’s the right thing to do,” Melvin says. “Sometime people don’t have advantages that they need and it’s just the right thing to do to give them an advantage. I think it helped some of them. It certainly gave them an opportunity to get ahead. And many of them they did.” Among those who have worked for Melvin over the years are men and women who are now doctors and lawyers, teachers and engineers.

He pauses when I ask him if he taught all these young people valuable life lessons. He slowly shakes his head. “I don’t know that they’ve learned anything from me directly,” he says. “I think they’ve learned how life can treat you and what you can accomplish in life if you work at it. I don’t feel that I’m an instrument of teaching; I feel like I’ve facilitated their ability to learn.”

Melvin does tell me that any time one of his long-term employees leaves the shop, he feels a certain pang. “They become part of the family and when they leave it’s like a child leaving your home,” he says. “It is hard, but it’s also normal.”

Periodically one of his old employees does return for a visit. “I see a few of them,” says Melvin. “Just recently there was a boy that worked here in the mid-seventies. He’s been down in North Carolina for years, raised a family down there, and he was coming through town on business and stopped in the store out of the clear blue just to say hi and talk about old times. I liked that. In all the years I’ve owned Fin & Feather I’ve never had a bad kid.” He smiles at his own words.

When I ask if he has any regrets, Melvin says, “I’ve led a good life. I’ve managed to run a successful business. I’ve kept a roof over my head. I think we all could say we’d like to change some things, but it’s petty. My one regret is not having kids of my own.”

When I talk with Melvin later and mention the possibility of retirement he shakes his head. ”My health is steady so I don’t want to stop working,” he says. “I don’t want to be the old fellow that sits at home and stares out the window.”