Night Noises

By Charles McGuigan 11.2020

“Everything can change just like that.” But there is no snap of fingers. This is the preamble to a story Jane’s retold a hundred times in person or on social media. The beginning of the story is always jarring, but it’s the end that leaves people speechless.

Jane has it all. She knows it, too. Not one member of her family has been struck down by COVID. She and her husband Marty still have work, and are able to help their ten-year old son navigate school during the pandemic. Their other four boys are grown and making their way in the world. Marty and Jane and their offspring have health; they have good fortune; they have love. The house she shares with her husband and youngest son is perfect for them. They had the house painted a couple weeks earlier, and Marty screened in the side porch, and changed the deadbolt on the door off the porch so that it could be opened from the inside without a key. Marty’s a contractor and knows those locks can save lives if there’s a fire for instance; you don’t have to hunt for your key, just twist the thumb turn.

Early one morning when her story begins, Jane starts out of a deep sleep, eyes wide. She sits bolt upright in bed and stares at the door, which is open just a crack, casting a triangle of light on the floor. A noise woke her—a metallic and hollow clatter, the sound of trash being tossed into an empty dumpster. But the noise is an echo of a memory now. All she hears is Marty snoring and a steady rain pelting the roof. When the fog of sleep clears, Jane considers the pile of aluminum ladders stacked alongside the house. The painters hadn’t removed the ladders yet; they might have fallen. That would explain the noise. She wonders if someone tried to steal the ladders, so she rises from bed and moves toward the window. She can see nothing along the side of the house except the wet dark night, but above the sound of the rain and her husband’s snoring, she clearly hears voices.

Jane looks at her cellphone: it reads 4:45. She is not alarmed. It could be early risers; she’s left the house at this hour before. She decides to let their dog out in the backyard to do his business. Flash is a massive mastiff, and he follows Jane down the stairs. As she approaches the side door she can hear the voices. They are loud now, and someone is out there kicking the door and pounding at it with balled fists. Then Flash, all one hundred and fifty pounds of him, makes a beeline for the door. Jane can sense the rage boiling in his gut and the rumble of his will as he growls and lunges toward the door and the man standing on the other side of fifteen panes of 1/8-inch thick glass.

“Somebody’s coming in,” Jane yells, and now Marty is up and out of bed. He vaults down the stairs and stands behind the couch facing the side door. He hears the panes of glass rattling. “Get out of here,” he yells. Marty flies back upstairs and grabs a crossbow that has no arrow, along with an antique sword.

A pair of bare fists come crashing through the small glass panes, pulverizing them into shards and slivers that shower the room and cover the floor with a thin coat of jagged sleet. It seems to Jane the glass is shattering in every direction, and that there are several voices outside, so she races back upstairs to her son’s room. As she reaches his bedroom door her mind wanders into one of the darkest corners of Richmond’s recent past. Jane thinks of the Harveys, a family of four—husband, wife, two young girls—brutally murdered in their home on a New Year’s Day fifteen years ago during a grisly home invasion.

“There are multiple people coming in my house right now to kill my family,” Jane thinks, then shuts the door behind her. She calls 911 and frantically searches for a skeleton key that will lock the door in this old house, but she cannot find it. She comforts her son, all the while calling 911, but the call doesn’t go through. Jane thinks she hears people coming up the stairs. She leans against the door pushing all her weight into it, hoping this will deter anyone from breaking into her son’s room. She will later learn the noise in the hall and on the stairwell were made by Marty who has the build and look of a Russian kick-boxer.

Marty has no idea if the man on the other side of the door is holding a gun, so he keeps his distance. Gradually, he approaches the intruder and points the crossbow at his face. And then the man starts punching out the panes of glass again. There is no gun. The intruder’s hands search for the thumb turn of the deadbolt. That’s when Marty pulls the sword from its sheath, and begins hacking away at the hands that have entered his home. Each time Marty slashes one hand, it retreats, but then the other one enters. When Marty slices into that one, it pulls back, only to be replaced by the other hand. It’s like a game of whack-a-mole.

Now there is blood splattered everywhere. There are drops of it on the shattered glass, and it pools near the threshold where the intruder stands. In this predawn light it does not look red; it is dark blue, almost black.

And the intruder keeps screaming. “I’m comin’ in. I am coming in!”

“I got a gun, get the f**k out of here,” Marty yells. He’s looking right into the intruder’s face and can see his entire body. Marty sizes him up. He can’t be much more than twenty years old, and has a stocky build. At about six feet tall, he’s a couple inches shorter than Marty. The intruder wears no shirt despite the cold rain coming down, and bears a number of tattoos on his arms and chest.

Marty knows that he will use the sword in earnest if the intruder breaks through the door. And the sword blade is razor-sharp. Marty nicked himself with it years ago and still sports a scar from the wound.

The intruder just keeps coming back with his fists, and Marty fends them off with the sword. Throughout it all, the intruder is talking to two men who aren’t even there. Marty is convinced this young man is drugged to the gills—PCP he’s thinking—so he decides not to cause him bodily harm.

Upstairs Jane has finally gotten through to the police dispatcher. She barks her address into her cell phone, and begins a screaming dialogue with her husband.

“Get the gun,” Marty hollers.

“I’ve got the gun,” Jane roars back. “I’m coming down. The police are on the way. I’ve got a gun.”

Of course there is no gun, but the police are on their way. Had there been a gun, Jane knows the young man battering his way into their home would now be dead.

Jane looks at her son, huddled in his bed. She fights back tears, and yells into the phone. “Hurry, hurry, hurry. My husband’s downstairs fighting these people in the house.” The entire time there is glass breaking. It never stops. And Marty continues to yell at the intruder. Jane tells her son, “It’s going to be okay.”

Then the police dispatcher tells her the police have arrived. Jane checks her phone. She had been talking to the dispatcher for just five minutes, but it seemed like an eternity.

“Everything’s going to be okay,” Jane says to her son.

“Where are you?” the dispatcher says. “Don’t come out. Where’s your husband?”

Downstairs on the screened-in porch, the intruder backs away from the side door as soon as he sees the flash of blue lights. He faces the street and bends over the retro metal patio glider that backs up to one of the screened-in panels of the side porch. His hands grip the backrest and his eyes widen, almost in fascination, as he watches the intriguing pulse of blue light.

Marty runs through the house and as he opens the front door, the police, with weapons drawn, train their guns on him.

Instinctively, Marty raises his hands. “It’s not me,” he says. “He’s on my side porch.”

“Where? Where? Where?” the cops say in unison.

Marty walks slowly to the side of the house. “Right there,” he says, pointing at the intruder who is still transfixed by the flickering blue lights.

Jane remains on the phone with the dispatcher, who tells her it’s safe to come downstairs. “Hell no,” says Jane. “I’m not coming down until I know that there’s nobody in my house.”

It takes the police a good hour and half to process the intruder. An ambulance arrives at one point and paramedics wrap the intruder’s hands in bandages. The police move the intruder from the squad car to the ambulance and back again. They are having trouble learning the young man’s true identity. Jane just wants them gone. She doesn’t want to have to look at the young man, doesn’t want him or the cops in front of her house any longer. Time for them to go. When Jane is certain the house is clear, she goes to the bathroom and retches into the commode. Her life, she knows, will never be the same.

Later in the day, Jane and Marty sweep up the glass, and wipe down the floors and molding and walls with bleach and water, wiping away the blood, which had begun to congeal. They also sponge away the pair of bloody hand prints the intruder left on the backrest of the glider on the side porch. The water in the bucket is tomato red. And then Marty and Jane buy a gun and ammunition.

* * *

Every night after that, Jane lies awake in her bed, while Marty sleeps. Every creak, every footfall startles her and she calls out to her husband, “Did you hear that? Wake up. Go downstairs and check.” And Marty rolls out of bed, checks things out downstairs, and returns.

Jane simply doesn’t sleep at night. In the past when she woke late at night, she would sometimes go downstairs, get a glass of water, or let the dog out. Now she is terrified of leaving the second floor. Now when she can’t sleep, she paces around the bedroom, moving from window to window to see what is going on outside. At night, the downstairs terrifies her.

Sometimes at night she will look at the face of her son, at the smoothness of his features. She sees that his body is still and his breathing even. And then she thinks what he must have endured that night, and it calls to mind her own fears of a child. She remembers the nightmare, waking up and realizing someone had broken into their home. But for Jane, as a child, it was just a fear. For her son now, it is a reality.

Every day, Jane and Marty talk about that night of terror. It’s their way of getting through it. They also talk with their son. And here’s what Jane says: “This guy that broke into our house, we’re pretty sure was completely out of it on drugs. That’s somebody’s child, that’s somebody’s kid. He’s also somebody’s grandchild, somebody’s brother, somebody’s uncle. Maybe, somebody’s dad.”

Between themselves, Marty and Jane remember what they had done as young people. “When I was his age and in high school I didn’t do a ton of drugs, but I’ve experimented,” Jane says. “They told us it was acid he was on, it was not some hard drug, it was hallucinogenic, which normally most of us would watch the trees breathe, or watch a coffee cup breathe.” She considers the cup in her hands.

“Maybe he really would have just come in and sat on the couch,” Marty suggests. “Maybe he just needed to be inside in his drug stupor.”

Jane realizes they are trying to humanize this man who terrorized them. It’s not that they were softening, but they were trying to understand.

“I still want them to throw the book at him next week in court,” Jane tells her husband. Yet as a mother she also understands the young man could have been one of her own boys. “One of our five boys could get in trouble someday,” she says. “Might have gotten into trouble. Who knows? None of us are angels. Everyone has their thing and if they haven’t done something, they know somebody or are related to somebody that’s done something stupid. Or they’re lying. Or didn’t get caught.”

* * *

Eight days after the intruder smashed their windows and their sense of safety, Jane and Marty, at nine on a Monday morning, find themselves in a courtroom. They survey the others there, but don’t recognize the intruder.

Then a young man with a very distinctive hair style walks in. Just beside him is a woman who looks to be about Jane’s age. Their eyes don’t meet. Jane nudges her husband. “That’s him,” she says. “That must be his mother. I hope they throw the book at him.” Marty nods.

Jane continues to watch as the woman touches her son’s shoulder, and something wells up in her, some new understanding. She looks over to her husband, and can see that he is watching the woman, too. “I feel really bad now,” Marty says. “Oh my God, I feel really bad."

The prosecuting attorney approaches Jane and her husband, and says, “This is what we’re going to do to make sure he gets prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. We will make it very clear that we will not accept anything except for jail time for him.”

Jane and Marty look at one another, and Jane raises her hand.

“Before we go that far tell me one thing,” she says. “What does he say about it? Has he shown any remorse? What does he say happened?”

“Okay, hold on,” says the prosecutor. “He actually has written y’all a letter. He would like to speak with you in person, would like to apologize to you in person, if it’s possible. He wants to pay you restitution. Would you be willing to let him speak with you?”

“Yes,” Jane says. “Let’s go.”

The three walk out of the courtroom and into a large foyer. The young man and his mother look both terrified and mortified.

The mother snuffles between deep sobs, and the young man’s cheeks are streaked with tears and his eyes are moist.

Without saying a word, Marty saunters over to the young man and shakes his hand.

“I’m so sorry,” this young man says. ”I’m so sorry for what I did to your family.”

And then Jane does something she hasn’t done with her own grown children since the COVID crisis started. She hugs the mother, wraps her arms around her. Jane rubs the woman’s back and can feel her trembling. Jane tries to soothe, rubbing her back even harder.

“It’s okay,” Jane whispers in her ear. “It’s gonna be okay.”

“I am so sorry,” this other mother says.

The prosecutor later tells Marty and Jane that the young man received a ninety-day suspended jail sentence. As the couple wait for the elevator, the mother and her son approach them. The young man hands them an envelope containing seven hundred dollars, and he can see a question on Jane’s face.

“I want you to have this money to pay for any damages,” he says.

“I don’t feel comfortable taking your money,” Jane says. “Your mom just came all the way here from Minnesota during COVID. I’m sure times are hard for everybody right now. Please take this money back. I don’t feel comfortable.” But the young man’s attorney insists, and Jane folds the envelope in half and she and her husband board the elevator destined for the ground floor.

Not long after this, Jane receives an email from the mother. She’s telling her husband about that email. ”She wanted to check in and see how we’re doing and see how our son is doing,” Jane says. “She wanted to let us know how sorry she was for everything and how sorry she was for how her son’s actions had affected our lives. She said let’s stay in touch and that she understands if I don’t write her.”

But Jane does respond, and then receives another email from this woman out of the Midwest. “She said she wants us to come out there when COVID’s over so she can show us around Minnesota and have a barbecue,” says Jane to her husband. “And someday we could do that, right? I could see us being friends in real life. Honestly. It’s so fricking crazy.”

That night, when her son is down, and Marty is asleep, she climbs in bed next to her husband, and nestles against his back, and she sleeps soundly.

Early in the morning Jane stirs in her sleep. She’s not sure what she heard or even if it was a noise that woke her. She holds her right hand to her chest and can feel her own heart, and thinks she can hear it, too.

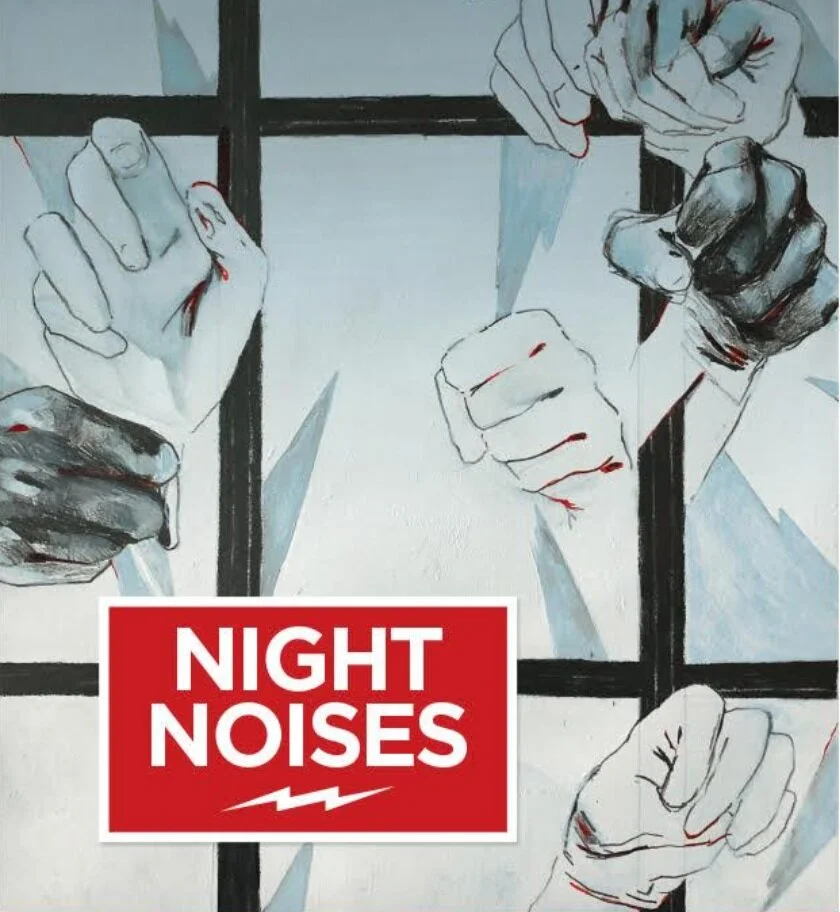

Cover image by Catherine McGuigan