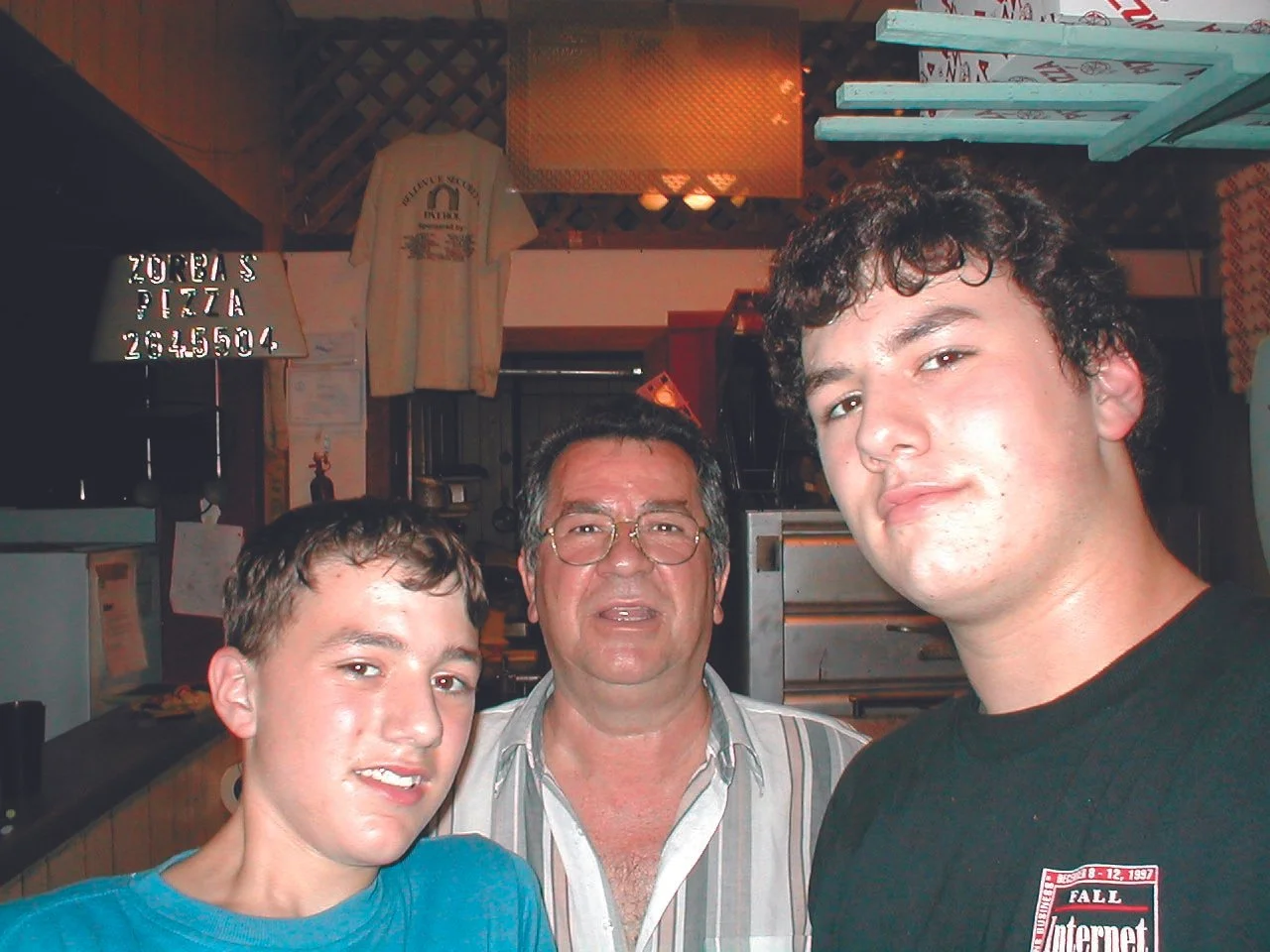

Tommy with two of his young employees.

Ode on a Grecian Urn

by Daniel Payne 08.2025

A generation of children in Bellevue grew up with Athanasios “Tom” Tolias, sole proprietor of Zorba’s Pizza and Subs on Macarthur Avenue. Tom was an indelible part of what we might at this point call Old Bellevue: A big, bluff, loud-spoken man, he was a fixture in the vast firmament of the neighborhood’s cast of characters for nearly two decades, the kind of human staple whose indelibility, already obvious at the time, only grows in retrospect.

Tom has been gone from MacArthur for over a decade, and dead for nearly three years. Now Zorba’s, too, is going, due for re-branding this September, though the new proprietors will continue to serve pizzas and other dishes that came out of the kitchen there for more than three decades. The mark Tom left on the lives of the few people around Richmond who knew him will endure. He was, in his own inscrutable way, a great and profound teacher, a man whose lessons have served us well for years and will serve our own children in turn. Tom embodied well that great Greek proverb: A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit.

Tom claimed to have joined the Merchant Marine in Greece and to have eventually jumped ship in New York City. We never knew if this was true, though ultimately it did not matter; the story added to his gruffly romantic mystique, and it was funny. He told a story about disembarking in New York in the 1970s and shortly thereafter encountering a group of hippies who greeted him with a volley of peace signs. Unaware of their pacific intent, Tom responded with a gleefully rude hand gesture. This was, he claimed, the outset of his life as an American.

Tom was an American, regardless of any real or apocryphal stories of his arrival. He was an American who embodied what President Harry Truman said was the uniquely American tendency of “an unbeatable determination to do the job at hand." We learned a little more about him over the years, including that he had family down in South Carolina.

We knew this much, or at least this much he told us: At some point in his life he had run a restaurant with his cousin and his brother; a fire had broken out there; both his cousin and his brother died, while he barely survived. A patchwork of skin grafts up one of Tom’s arms marked this brutal episode in his life. He rarely spoke of it.

Rarely, but not never—and sometimes to grimly wry effect. One night in the shop, a customer came in to pick up a pizza; Tom was occupying his traditional chair in the front of the shop, holding court with whoever came by, and this man sat down next to him to wait for his order. For some reason Tom chose to tell this fellow the terrible story of his burned arm and how he had acquired it.

But Tom’s accent was gruff, Greek, almost guttural; for outsiders, those not accustomed to his way of speaking, he could at times be impossible to understand. The customer did not grasp the enormity of the story Tom was telling him. Awkward and unsure, he decided to laugh instead. “That’s great, Tom!” he said while guffawing.

Tom stared at him, his eyes bulging. “It’s no funny, man!” he barked. The fellow only laughed harder, trying manfully to please this growling figure before him. “Ahh, forget it!” Tom said, waving him off.

The history of Tom’s life before Zorba’s may have been indecipherable. But his life at Zorba’s was perfectly clear: He did little but work. He usually showed up at the restaurant in the early afternoon, sometimes the late morning; before that, we knew, he sometimes met a group of Greek-American friends at Willow Lawn for coffee.

He seemed to do little else. To be sure, it is not quite right to say that he lived to work. He was not exactly a Ponos, that ancient Greek god of toil and labor; he was closer to an Aion, cyclical and eternal, always coming around to the same thing.

Even his home life was austere. On the rare occasions we visited his home in Mechanicsville, we saw that though he had lived there for years, his house felt barely occupied. A couch and a television. A few stray pieces of furniture. A refrigerator with barely anything in it. A bed upstairs. It seemed as if he spent almost no time there and had little interest in any domestic embellishment. It was wholly Potemkin.

Most nights at the shop Tom made his own dinner, often flash-searing a fish in the oven with potatoes and green vegetables, while the rest of us ate subs or pizza. But at least once a year, always in the winter, he would laboriously assemble a bean soup, starting from scratch with dried beans and slow-cooking them all day long. It was flavorful and liberally spiced; he cooked it in a giant pail. We would feast on it for days, slurping it up and sopping up the stock with house-made breadsticks. It is still among the finest soups any of us has ever had.

Most of us got our job at Zorba’s in the same way: Tom would see us—on the street when he drove by, when we came in to pick up a pizza or sub, or while walking by the restaurant—and he’d yell out: “You come in tomorrow, I give you a job!” There was no question of rejecting this invitation. At Zorba’s the offer of a job and the acceptance of it were indistinguishable.

Working in Tom’s kitchen, you were taught how to work. It was harsh, and fast, and unsparing. It is not enough to say that it was “old-school.” It was almost proto-school, a culinary education from a time when there was no education and no cuisine. Those who could withstand Tom’s completely antagonistic on-the-job training emerged as really capable workers. Those who could not—and there were many of them—were fired, or quit outright, or else just ceased to come in, never to be seen again.

Tom lived entirely by the narrative maxim: “Show, don’t tell.” If you were doing something wrong in his kitchen—chopping the tomatoes sloppily, assembling salads too slowly, mincing garlic too diffidently—he would watch you for a moment, shoulders hunched, eyes narrowed; then he would grunt, shove you aside, grab the knife or the tub of lettuce, and say: “You do it like THIS!”

He would teach you how to make a pizza the same way: You might be stretching out a ball of dough lazily or too timidly or hesitantly or in an oblong shape, and he would elbow you aside, mash the dough out roughly, stretch it on his upturned fists, sauce it with an aggressive splattering of marinara, and throw it into the oven. “Like THAT!” he’d bark. Rough as it sounds, many of us still use Tom’s practical instructions in our own home cooking even decades later.

Payday at Zorba’s was always a primal, almost Dionysian affair: Tom would add up our hours from the week before, we would line up at the counter, he would take a gigantic wad of cash from his back pocket, and he would peel off and pile up a series of bills—20s, 10s and 5s—giving each of us our weekly take. It was easily the most public and transparent act of payment any of us has ever experienced. There was a geniality to all of us, each of us scooping up our pile of cash, everyone in high spirits. And you felt too as if you had really impressed this broad-chested, growling immigrant fellow whom you worked for—you had proved your mettle, at least for another week, and he had paid you for it. No other wage has ever felt quite so primeval, so cardinal and so unique. It was not a lot of money, but it was good money.

Tom was unflappable. He was probably the canniest, shrewdest man any of us has ever met. He was always skeptical, ever watchful, his guard always up, his aspis never lowered. It is hard to explain. It might be best to say that he was just a permanently suspicious man, always half-mistrustful of everybody and everything, Suspicion, Robert Burns wrote, “is a heavy armor and with its weight it impedes more than it protects.” We all had fine working relationships with Tom, but he kept everything and everybody at arm’s length. That was how he liked it.

At times it seemed a lonely life. In other cases it served him well. He seemed, in some odd sort of way, unbeatable—you never seemed to come out on top with Tom, even if nothing was at stake.

One example: At some point Tom left us in charge of the restaurant when he went on a trip to visit family. We made a copy of the master key—”Just in case,” we said—and some months later we used it to sneak into the restaurant after hours for an April Fools’ Day prank.

Tom kept a mountain bike in the shop that he used to bike around the neighborhood, and we had purchased a glittering, frilly girl’s bike from a thrift store. We brought that into the shop, dismantled Tom’s bike, and replaced most of the components—the wheels, the handlebars, the velcro straps—with those of the purple, tassled, spangly little bike we had bought.

The next day we came in for work and found Tom sitting complacently in his chair. “Okay boys,” he said with a chuckle. “Fix the bike.” We all had a laugh and went to put his bike back together. But then we discovered that his bike wheels were missing; we had carefully stashed them the night before but could not find them now. We desperately scrabbled around for them, growing more and more panicked, as Tom grew more and more aggressive in demanding that we fix his bike. We were at a loss.

Finally Tom roared with laughter and showed us where he had hidden his own bike wheels from us, just to induce in us a bit of hysteria. He had hoisted us with our own petard.

Tom eventually sold the shop and moved to South Carolina to be near family. He long ago became the stuff of leaf-fringed legend, of folk tale—a man whose endeavors and exploits are woven into the fabric of local mythology. Perhaps that’s a fitting legacy for this man, a guy who once allegedly jumped ship and made a life for himself in a new land and did whatever it took to survive here, a real embodiment of the Greek polytropos. Almost a myth, except it was all (mostly) true.

Over years of memories with Tom, one often sticks out. Our father died in June of 2000; his last outing, just weeks before his death, was at Dot’s Back Inn with his sons for lunch. Unbeknownst to us, his brain tumor had returned; he had a seizure at Dot’s; an ambulance came to take him to the hospital.

While we waited for the ambulance, as our father was seizing upright in the booth, Tom — who was eating lunch a few booths back — came over to speak to us. “Billy, I see you here having lunch with your boys!” he shouted cheerfully at our father.

When it became clear that our father was in a dire medical emergency, Tom’s face went pale. As the restaurant staff swarmed around trying to help, Tom quietly backed up, silent, his mouth slightly ajar. Finally, amid the confusion, he turned silently and walked out.

He later told us that he could not bear to see our father in such distress, that it pained him and he had to leave. It was an uncharacteristically vulnerable gesture from a man usually known for gruff, cheerful bluster.

And he responded to that crisis in maybe the only way he knew how: with good, honest work. On nights when we’d be working the shop, customers would come in to pick up their pizzas and Tom would point proudly to his bustling workforce behind the counter. “You see these boys?” he would say. “Their father die years ago, very sad, I say to myself, ‘I keep them busy, I give them jobs!’”