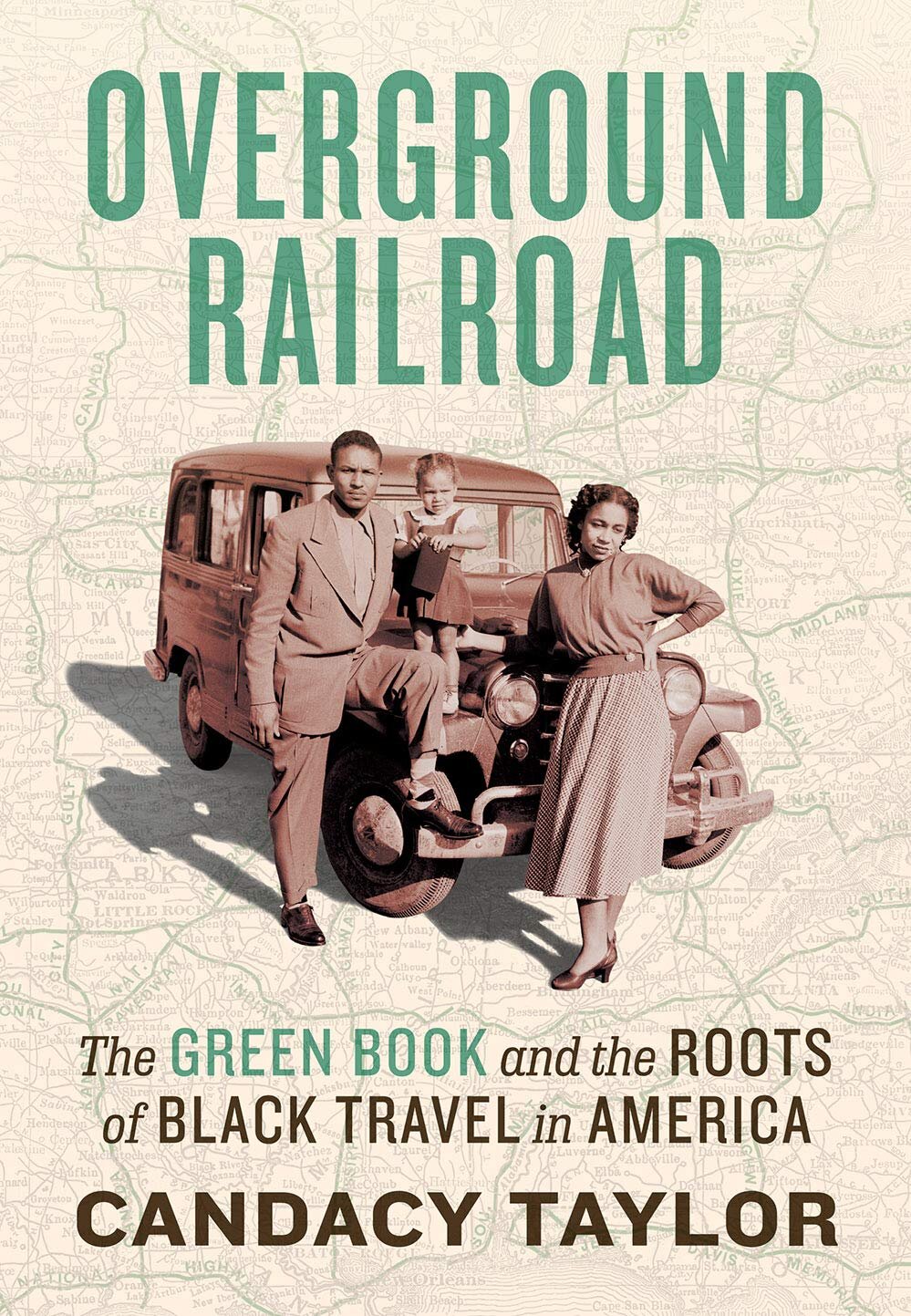

“Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America”

By Candacy Taylor

Abrams Press

360 pages

$35.00

The Overground Railroad

by Fran Withrow 09.2021

When I was small, my family would drive from West Virginia to New England to visit our cousins. Sitting in the back seat of the station wagon with my squirmy siblings, I never worried that gas station owners might refuse us service, that we might be unable to find a restroom we would be allowed to use, or that we would not be welcome in any restaurant we wanted to patronize.

This example of my white privilege was brought home to me repeatedly as I read “Overground Railroad,” Candacy Taylor’s revealing account of Black travel from the 1930’s through the 1960’s.

From the 1930’s on, many Black families could finally afford a car. This freedom, however, presented them with new challenges as they continued to face racism throughout the country. These new auto owners toured the country anyway, planning for contingencies by packing their own food as well as emergency toileting supplies. They brought blankets with them in case they were denied hotel entry and forced to sleep in their cars. And they hit upon ingenious methods for protecting themselves if they encountered an antagonistic police officer.

For many Black families, another essential travel item while on the road was the “Green Book,” a travel guide for Black tourists published originally by Victor Hugo Green in Harlem. Green had only a seventh grade education, but he went on to print the “Green Book” from its inception in 1936 until his death in 1960. The travel guide continued to be distributed under the tutelage of his widow and others until 1967.

The “Green Book” was a lifeline for Black sight-seers, listing a variety of safe places to visit while on the road. Black-owned restaurants, hotels, garages, beauty parlors, and night clubs were among the amenities listed for each state. With this guide, Black drivers could rest assured that, as long as they could get to the places found in the “Green Book,” they and their money would be welcomed with open arms.

The chapters in Taylor’s book are divided by year, and she blends discussion of what was in the travel guide for that year with what was going on in the country during that time. Taylor traveled the country as part of her research, documenting as many of the remaining Green Book listings as she could. (Many sites are gone or have fallen into disrepair.) Her book brims with photos of some of these places, including a snapshot of each “Green Book” cover.

Taylor talked with many people, including her own stepfather, who reminisced about travel during those turbulent years. It is obvious that it took ingenuity, courage, and a lot of planning for Black travelers to take to the road. The "Green Book,”which eventually expanded to include international travel, was a valuable tool for these intrepid drivers.

Taylor’s insightful, informative book shows how far we have come in the fight for justice and equality for Black people.

And also just how far we still have to go.