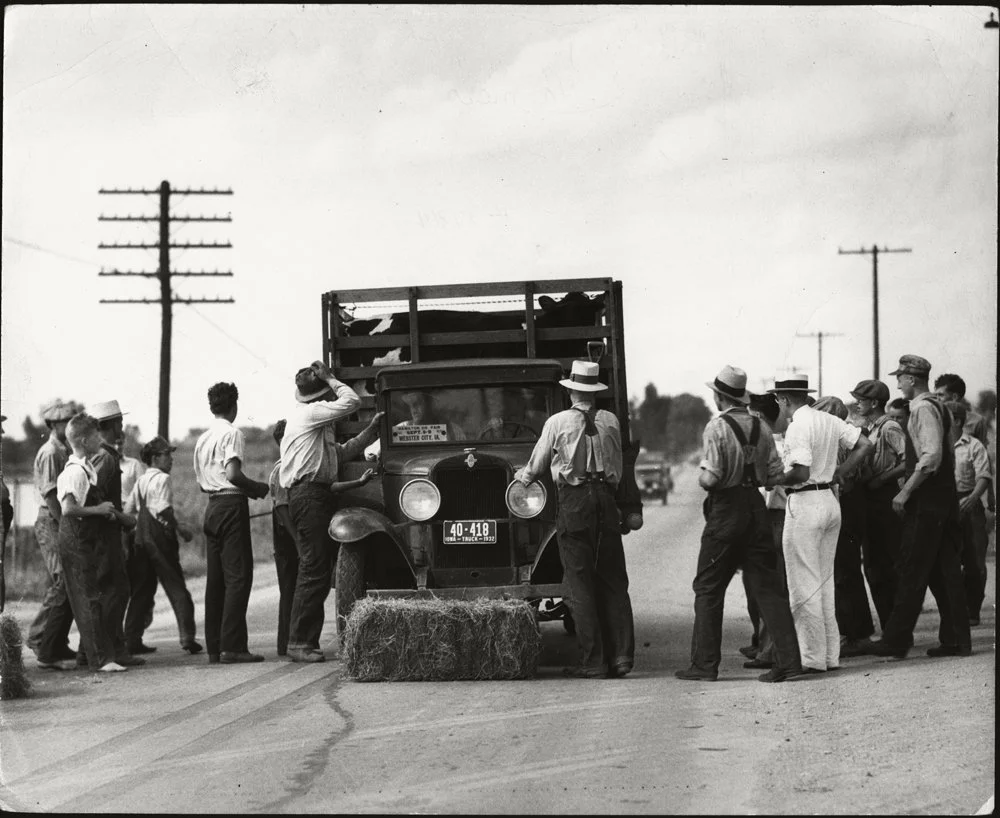

"Farmers Strike," 1932. Image courtesy of State Historical Society of Iowa.

The First Farm Bill, the Farmers’ Holiday Association, and Penny Auctions

by Jack R Johnson 11.2025

Arguably, the most violent agricultural movement in U.S. History, the Farmers’ Holiday Association (FHA), arose out of Depression era farmers' frustration with the cost of production, low market prices, and a bank’s foreclosure stealing their livelihood and their land. One technique the Farmers’ Holiday Association used to keep the banks from taking the farmers’ land was a communal effort of understated violence, the so-called 'Penny Auction.'

By the time of the stock market crash of 1929, life was already extremely difficult for Midwest farmers. During World War I, demand for farm products skyrocketed because of the war and the U.S. government guaranteed prices for farm products to supply the army. To meet the demand, farmers increased their acreages and expanded their herds, borrowing money if necessary; and for a few years, they enjoyed a rare prosperity. But with the war's end, the government no longer guaranteed farm prices, and they fell to prewar levels. Farmers who had borrowed money to expand during the boom couldn't pay their debts.

After the stock market crash, things became dramatically worse. Farmers were still producing more food than consumers were buying, and now consumers could buy even less. According to David Walbert, writing for NCPedia, “Cotton had sold for 35 cents a pound in 1919 but only 6 cents a pound in 1931. National farm income fell from a high of $16.9 billion in 1919 to only $5.3 billion in 1932.” In some cases, the price of a bushel of corn fell to just eight or ten cents. Some farm families began burning corn rather than coal in their stoves because corn was cheaper. Sometimes the countryside smelled like popcorn from all the corn burning in kitchen stoves.

As farms became less valuable, land prices fell, too, and farms were often worth less than their owners owed to the bank. Farmers across the country lost their farms as banks foreclosed on mortgages, an action that was deeply unpopular.

In February 1932, Glen Miller, a writer for the publication Iowa Union Farmer, argued that Iowa farmers should declare a "holiday" in which “farm products would be kept at the farms where they were produced until politicians and the general public began to appreciate the importance of farmers.” Three thousand farmers who gathered in Des Moines, Iowa, in May 1932 to found the national Farmers' Holiday Association cheered the idea. The group consisted primarily of farmers from Iowa, but also included farmers from Minnesota, Nebraska, Illinois, and Wisconsin, as well as many other states. In August 1932, members of the FHA launched the first withholding protests in Sioux City, Iowa, picketing along highways and threatening farmers who refused to cooperate and were attempting to bring their goods to market. The farm strikes quickly spread to other Mid-Western states as members of the local Farmers' Holiday Associations in those states began to stage their own protests. The Farmers’ Holiday Association also focused its attention on preventing farm foreclosures through what came to be known as ‘Penny Auctions.’

The FHA took a lesson from an incident that first occurred in 1931. About 150 Nebraska farmers showed up at a foreclosure auction at the Von Bonn family farm. The bank was selling the land and equipment because the family couldn’t repay a loan. “The bank expected to make hundreds, if not thousands of dollars.” The auctioneer began with a piece of equipment. The first bid was 5-cents. When someone else tried to raise that bid, a farmer requested him not to do so, forcefully. Item after item got only one or two bids. All were ridiculously low. The proceeds for that first Penny Auction were $5.35, the only money the bank would see to pay off the loan. The idea caught on. According to Working Class History, Harvey Pickrel remembers going to a Penny Auction where “some of the farmers wouldn’t bid on anything at all – because they were trying to help the man that was being sold out.” At auctions across the Midwest, farmers showed up as a group and physically prevented any real bidders from placing bids. Nooses decorated barn rafters as a deterrent to anyone trying to raise the bidding price.

Sometimes, the farmers were even more direct. In Le Mars, Iowa, a mob of angry farmers burst into a courtroom and pulled the judge ordering foreclosures from the bench. Judge Bradley asked the men to take off their hats and to stop smoking. The farmers shouted: "This is our courtroom not yours." They ordered Bradley to promise not to foreclose, or sign any more foreclosure proceedings. He refused. A farmer slapped him. Bradley was ordered again and he refused and was slapped again. Then the farmers took him to a crossroads out of town and placed a rope around his neck. “A telephone pole was used as the ‘hanging tree’ and he was lifted from the ground by the taut rope. At this point, the farmers became involved in an argument concerning the relative merits of hanging as opposed to being dragged behind an automobile. They settled the incident by taking off the Judge's pants, filling them with grease and dirt and then leaving the scene." Bradley eventually received a ride into town and returned to his home. His neck was burned from the rope and his lips were bloody and bruised. The National Guard arrived in LeMars the next day.

Eventually, several Midwestern states, including Nebraska, enacted moratoriums on farm foreclosures. Following Franklin D. Roosevelt's Presidential election in November 1932, leaders of local FHA organizations in several Mid-Western states met in Omaha, Nebraska, to discuss the potential effect of Roosevelt's presidency on the plight of the farmer. The convention crafted a resolution that called for the suspension of strikes and blockades of farm commodities to give the new president sufficient time to act on their concerns.

Less than a year into his term, President Roosevelt delivered. He signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 -- which set limits on the size of the crops and herds farmers could produce. Those farmers that agreed to limit production were paid a decent subsidy. Most farmers signed up. “Soon government checks were flowing into rural mailboxes where the money could help pay down bank debts or tax payments.”

This was the first "farm bill" in U.S. history, and it introduced a new era of government support for agriculture that continues to this day.