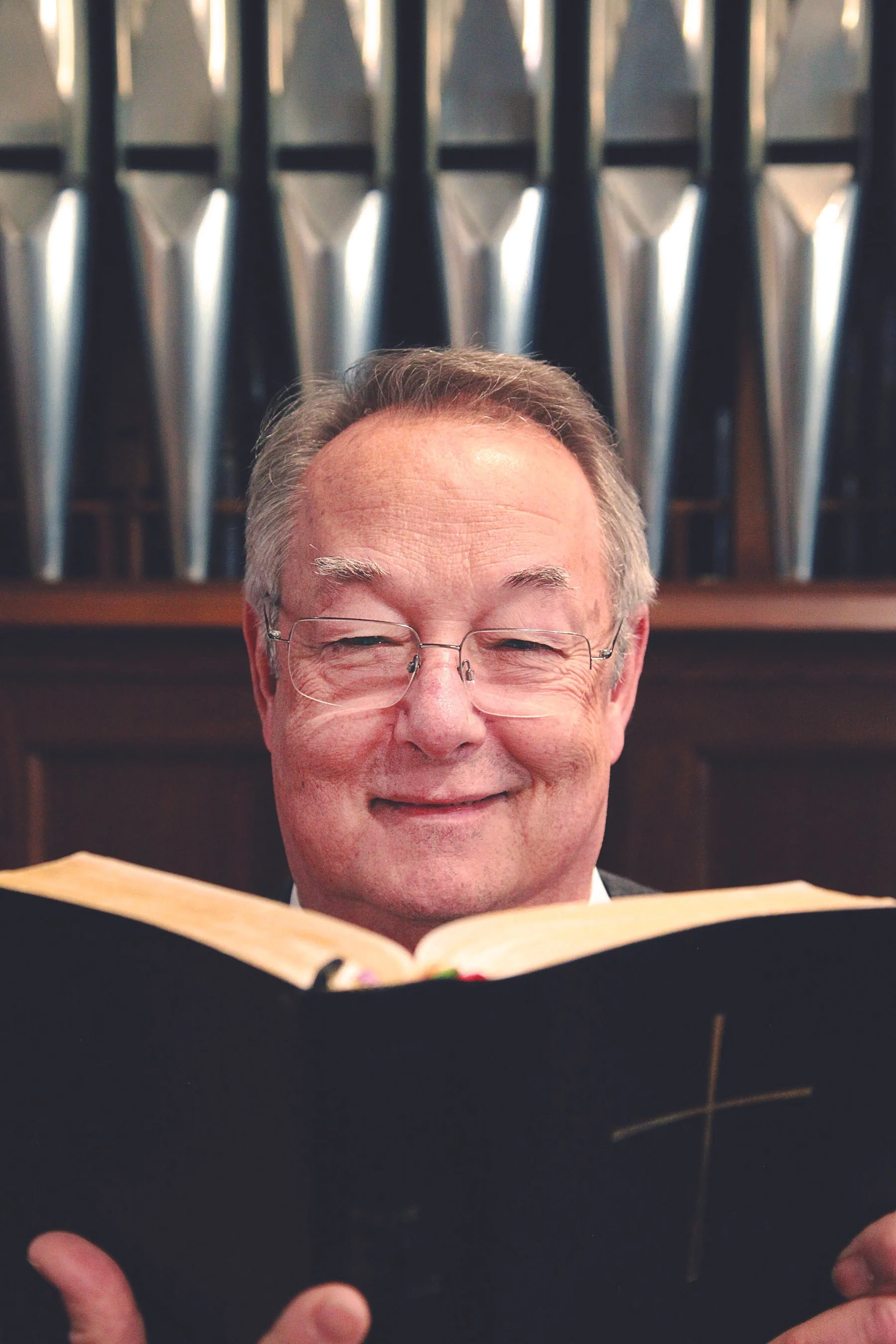

Rev. Herbert Jones. Photo by Rebecca D’Angelo

The Rev. Herbert Jones: God’s Beloved Child

by Charles McGuigan 12.2025

Central to the message of all major world religions is a call for compassion and peace, and, above all else, love. This is not true of the bastardized versions of these belief systems that flat out reject the basic principles clearly laid out in sacred texts. Those who so distort these foundations often do so to create discord, and use religion as a means to enrich themselves and gain political power. That is not the case with an Episcopal priest in Richmond’s Northside. He is humble and joyous with a great sense of humor—a man who received the call later in life.

Herbert Jones wouldn’t come to the ministry until around the time he had lived for half a century, though even as a child he had been enamored of the priesthood. But time and again he rejected this road in life.

It all started when he was just eight years old. At the time, his mother had recently become Episcopalian. She had joined Church of the Redeemer on the Southside and Herbert served on the Junior Choir. From his vantage point during Mass he had a very clear view of Rev. Joe Pinder as he offered the Eucharistic prayer. He was fascinated by the priest’s hands and his face, and thought he knew then and there what he wanted to do when he grew up.

At home, later that day, he told his father what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

“I want to be a priest when I grow up,” he said.

His father, a pediatrician, gave his son a quizzical look, and shook his head.

“No you don’t,” he told him. “Priests are kooks. Priests don’t have their feet on the ground, they run around with their head in the clouds. You want to be something practical. A doctor or a lawyer.”

Herbert sits across from me at a long table. Later in the day I will join him again at the church where he is rector—St. Thomas Episcopal, which is home to one of the most amazing food pantries anywhere.

He considers the words his father said to him about the priesthood all those years ago. “I was eight, so I believed him,” he says. “Looking back on that, I think that’s why I just sort of floundered. I was floundering for a lot of years. Every now and again, the priest thing would come up, and I would think about doing it, and then it just didn’t happen for me.”

But throughout his life he was always moored, in one way or other, to the Episcopal Church. For instance, he spent five summers in his late teens and early twenties working as a camp counselor at Shrine Mont, an Episcopal retreat and conference center in the mountains near Orkney Springs. He taught white-water canoeing and in the evenings he’d pull out his guitar. “And I’d start playing the guitar and singing Jesus songs.”

Margaret Arnette Woody directing traffic.

After graduating from Maggie Walker High School, he attended Virginia Commonwealth University.

“I was on the thirteen year college plan,” he says. “I went to VCU a couple of times and I learned how to drop classes before I flunked out.” He then attended Ferrum College, just below Roanoke. “I majored in a whole bunch of stuff during the time I was in college, philosophy, pre-med, you name it,” he says.

He would ultimately earn a degree in economics from Randolph-Macon up in Ashland, and then head directly to law school at William and Mary. After passing the bar he went to work for a firm in downtown Richmond that specialized in real estate law and in insurance defense.

“That did not suit, it was not a fit,” says Herbert.

He ended up hanging his shingle on Robinson Street in the Fan. He began a general law practice, but fairly quickly started taking indigent criminal defense cases. “I was not a public defender,” he says. “I handled criminal cases for people who couldn’t afford a lawyer.” From there he began working on cases in juvenile and domestic relations court. And that led into a more specialized field. “Near the end I was doing criminal defense,” he says. “I was handling more serious cases like children who are being tried as adults.”

One of those cases had a profound effect on the course of Herbert’s life. It was an extremely brutal crime that involved four juveniles who would eventually be convicted of rape, sodomy, abduction, and robbery.

It was a highly publicized case, and Herbert wanted to defend one of the teenagers who had been charged. So he went to the scene of the crime on Libby Hill with a notepad in hand and began taking notes, reconstructing what might have happened there.

As he was walking, thinking about the crime, he heard a voice that derailed his train of thought and stopped him dead in his tracks.

“For lack of a better term, it was a God moment,” he recalls. “The voice said, ‘What the f**k are you doing here?’ I believe God speaks to us in a language we can understand, and that was the language that I was thinking in. And I had been talking and thinking about going to seminary for a while. ‘One of these days I’m going to go to seminary,’ I’d tell myself. I was approaching fifty. And I answered that voice on Libby Hill. ‘Yeah, what am I doing? This is not what I’m supposed to be doing.’”

Not long thereafter, Herbert began studying for the ministry, first at Union Theological Seminary (UTS) in Ginter Park, and then finishing his last year at Virginia Theological Seminary (VTS) up in Alexandria. And fourteen years ago, almost to the day, Herbert Jones was ordained a priest at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in the West End.

In the sanctuary on a Food Pantry Thursday.

While studying at UTS here in Richmond, he interned as a minister at Christ Ascension in Rosedale. And while at VTS he interned at the old Fork Church in Hanover County. The summer before his ordination, Herbert served as deacon in charge at the Church of Our Saviour in Montpelier, out in western Hanover County. And when he was ordained he became the vicar there where he would remain until 2017, when he became rector at St. Thomas.

Reverend Jones then tells me a little about his parishioners and the church he serves. “We are a very progressive parish and our members are progressive,” says Herbert. “And we’re getting a lot of new people now, younger people with families. It’s gratifying. I think a lot of it has to do with our progressive values and we make that clear.”

He mentions same sex partners and trans couples who had been ostracized from their evangelical churches—how absurd it is for any purported Christian denomination to do such a thing.

And then he tells me this, quoting from the Episcopal Church baptismal covenant:”Will you strive for justice and peace among people and respect the dignity of every human being.”

“That’s exactly what we do, and that manifests itself in our welcoming, and our food pantry,” he says.

He repeats the words from the baptismal covenant, and then says, “That’s not new woke stuff. That’s our promise, and it is woke.”

He mentions different sects that corrupt the central messages of the faith. “I was watching something about the prosperity gospel last night and they were showing some of these people preaching,” he says. “They talked about planting the seed. ‘Instead of paying that credit card bill give me a thousand dollars and that will plant the seed for you to have more money later.’”

Herbert shakes his head and his mouth curls into an ironic smile. “When people talk about the bad guys they would assume I would be talking about atheists,” he says. “Not at all. The bad guys are the people who take a beautiful story and manipulate it into something that helps them control other people.”

Volunteer Georgette Richards.

And the whole notion of Christian nationalism and tearing down the wall that separates church from state is something that raises Herbert’s hackles as both a lawyer and a man of God. “I have very little warmth when I hear things like a joint effort between the church and the government,” he says. “That shouldn’t happen. I want them to do their thing, and we’ll do our thing. As a lawyer, I very much believe in the constitutional principle of the separation of church and state. Nowadays, maybe you think it only protects the church, but that’s not what it’s about. It protects the state and that’s why it needs to be there. And you can be a good Christian and work for the government, and you can be a good Muslim and work for the government, all of those things, but you can’t use the government to force your stuff on the citizenry.”

When we talk about how some ministers from the pulpit openly condemn people because of their sexual orientation or ethnicity or different religious beliefs, he quotes the ancient theologian Irenaeus: “The glory of God is a human fully alive.”

He talks about ICE and some of their heavy-handed tactics, and the seeds of fear planted by politicians to fan the flames of xenophobic nativism. He reminds me how straightforward Christ was in his preaching. He didn’t mince words. Herbert mentions the parts of the New Testament that are essentially direct quotes from Jesus. “If you read the red letter part, it’s not at all hard,” he says. “It’s pretty clear and it doesn’t have anything to do with prosperity. Love God, love your neighbor. Pretty simple. And the world is your neighborhood.”

* * *

At 2:30 pm on the dot I arrive at St. Thomas Episcopal and there is already a steady line of cars, nose to bumper, down Hawthorne Avenue and along Walton. Margaret Woody directs traffic, and I find a place not far from the entrance to the parish hall.

Within, there are scores of volunteers helping clients with their groceries, and Herbert is in the sanctuary where folks are gathered waiting their turn to go to the parish hall. Later, Herbert shows me where they store the food, where the refrigerators and freezers are located. This is like a full-fledged grocery store, and I’ve never seen anything quite like it.

“I call it the weekly miracle,” Herbert tells me. It’s sort of like the miracle of the loaves and fishes, only in reverse. There’s tons of food in the beginning, but by the end of the day the larders are bare.

Volunteer Katherine Goodpasture lends a hand.

To get ready for the multitudes requires careful coordination, and a lot of hard work. Thanks to the efforts of the director and the diligence of the volunteers (who fill 140 slots over six shifts each week) things go off seamlessly. Food for distribution comes in from a variety of sources including Sam's Club, Walmart, Costco, Kroger, Food Lion, Montana Gold Bread, along with fresh produce from Seasonal Roots and Shalom Farms.

“Tuesday night the volunteers come in and set up the tables, and on Wednesday morning the FeedMore truck arrives,” says Herbert. “Then different people start bringing in all this other food on Wednesday and even on Thursday morning.” At 1:30 pm on Thursday Herbert and the volunteers form a circle where they exchange greetings, and thirty minutes later they’re handing out food. “By six o’clock Thursday evening it’s completely empty, the food is all gone,” Herbert says.

It’s a lot of food, too.

“So in 2024 we gave out 612,000 pounds of food and it will be more in 2025,” says Herbert. “So far in 2025 we have served 24,182 households and 54, 357 individuals.” Each week they give out more than five tons of food. But it wasn’t always this way.

Before Covid struck, a busy Thursday would see about 75 people coming to the pantry. During Covid, the St. Thomas food pantry was one of the few citywide that remained open. They did drive-thrus where masked volunteers would deliver bags of food directly to a person’s car. During the pandemic shutdown, the pantry began servicing up to 250 clients each Thursday. “With Covid it grew and it’s grown ever since,” says Herbert.

Up until fairly recently, on average, the pantry served more than 500 clients weekly. “We had a few days where we served six hundred, but that was rare,” Herbert says.

What changed it all was the current administration’s plan to scrap SNAP benefits.

“The numbers grew after the threat of having SNAP benefits taken away,” says Herbert. “We hit a new record a couple weeks ago when we served 710 families.”

Sometimes he cannot believe his own good fortune, and he has the deepest gratitude for what he does on a daily basis, whether it’s celebrating the Eucharist or officiating at a funeral or a marriage, or working at the Food Pantry.

“I love the people I work with,” he says. “I love doing the work I do. If I get frustrated, I just take a step back and I say, ‘What are you frustrated about? Think about what you were doing twenty-five years ago.’”

Volunteers in the parish hall.

It was about twenty-five years ago that Herbert would down his last alcoholic beverage.

“This is obviously a huge part of my story,” he says. “I got sober April 3, 2001 and I didn’t get a DUI or anything like that. As we say in recovery, ‘I was sick and tired of being sick and tired.’ And I didn’t have a come to Jesus moment after I got sober and say, ‘I’m going to become a priest.’ But I couldn’t have become a priest if I hadn’t gotten sober.”

He pauses for a long moment, and then says, “That began the comeback as it were. It opened up the doors for me. I started going to church, I became involved at St. James’s.”

And he made a deal with himself. “When I quit drinking, I told myself I didn’t have to quit smoking and I didn’t have to quit drinking coffee,” he says. “And then about four years into sobriety I thought, you’ve got to quit smoking, so I made another deal with myself that I had to quit smoking but I didn’t have to quit drinking coffee. I drink a lot of coffee.”

Sobriety led to something other than a metamorphosis. He was not changed. He emerged as he truly was all along.

“It was changing me into who I am,” says Herbert. “It just allowed me to become who I really am.”

“And who is that?” I ask.

“God’s beloved child,” Herbert says.