Revisiting Robert E. Lee

by Jack R. Johnson 12.2021

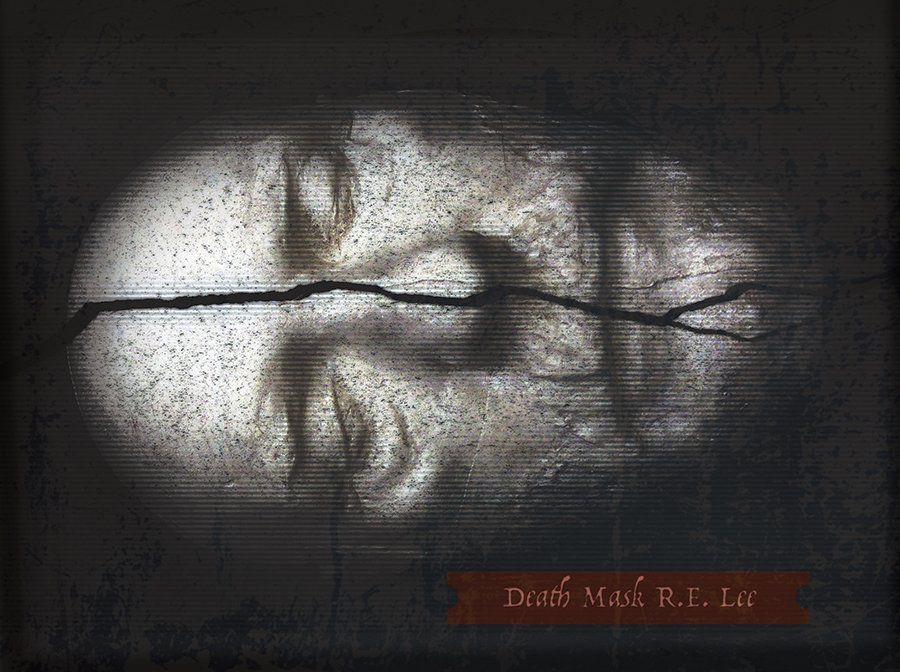

Cover graphic by Doug Dobey

They have taken down the monument to Robert E. Lee in Richmond, and soon they will remove the pedestal for Robert E. Lee. For many, this is a bittersweet moment. Thanks, no doubt, to the tireless efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and other proponents of the “Lost Cause” narrative. Their efforts have essentially recreated the General, while leaving the historical man safely entombed.

I, too, grew up reading about the ‘kindly’ General --I knew it was weird, but I didn’t know how weird at the time. There was a kind of breath-taking apotheosis of the man. Here’s a sample: one of Lee’s ex-generals, Jubal A. Early wrote this two years after his death: “Our beloved Chief stands, like some lofty column which rears its head among the highest, in grandeur, simple, pure and sublime.”

But, of course, once you get past that delusional reverence and read his actual history, you realize that Lee’s treatment of his own enslaved people, and Blacks, in general, could well fall into the category of plain old evil.

Let’s begin with his attitudes about race. He was a proponent of white supremacy: that was one of General Lee’s most fundamental convictions—and his fatal flaw; it was not ancillary to his efforts as general of the Confederacy; it was core.

Some folks point out that he once wrote a letter to suggest slavery was a moral and political evil. There’s some truth to that, but read the full letter (https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2010/08/arlington-bobby-lee-and-the-peculiar-institution/61428/), Lee considered it a greater evil to the white master than the enslaved Black. In short, slavery was another of the white man’s “burden”—an institution he quite usefully employed himself, presumably for profit as well as the ‘uplifting of the black race.’

Here are some examples of his general attitude.

Lee told Congress that Black people lacked the intellectual capacity of white people and “could not vote intelligently,” and that granting them suffrage would “excite unfriendly feelings between the two races.” Lee explained that “the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.”

“Well,” his defenders might say, “Lee was a man of his time and place: that was the current attitude back then. He was just misguided, but truly, he `was a good Christian man, and gentle to his slaves.’”

No, alas, he may have been Christian, but he was neither kind nor just to his enslaved people, even by the letter of the South’s own oppressive laws on the matter.

In Reading the Man, the historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s portrait of Lee through his writings, Pryor writes that “Lee ruptured the Washington and Custis tradition of respecting slave families” by hiring them off to other plantations, and that “by 1860 he had broken up every family but one on his estate, some of whom had been together since Mount Vernon days.”

Pryor notes that the way Lee treated his enslaved people nearly led to a slave revolt. They had expected to be freed upon their previous master’s death.

John Reeves, a historian and author of the book, “The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee: The Forgotten Case Against an American Icon,” said that Lee wanted to work the slaves beyond the five-year limit stated in his father-in-law’s will. Lee fought in court to keep the slaves working because he didn’t know if he would be able to pay off his legacies otherwise.

Wesley Norris was one of those slaves. He was born a slave on the plantation that Lee managed after his father-in-law died. Norris testified during the court fight that Lee beat him when he tried to run away. Wesley Norris recalled that “not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done.”

It wasn’t just his own slaves that Lee fought tooth and nail to keep enslaved. Pryor writes that “evidence links virtually every infantry and cavalry unit in Lee’s army” to the abduction of free black Americans, “with the activity under the supervision of senior officers.”

According to Adam Serwer, writing in the Atlantic, “Soldiers under Lee’s command at the Battle of the Crater in 1864 massacred black Union soldiers who tried to surrender. Then, in a spectacle hatched by Lee’s senior corps commander, A. P. Hill, the Confederates paraded the Union survivors through the streets of Petersburg to the slurs and jeers of the southern crowd. Lee never discouraged such behavior. As the historian Richard Slotkin wrote in No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, “his silence was permissive.”

Even as president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University), Lee’s unflagging white supremacist attitude held sway. According to Pryor, students at Washington formed their own chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, and were known by the local Freedmen’s Bureau to attempt to abduct and rape Black schoolgirls from the nearby Black schools. There is no record of Robert E. Lee ever disciplining students for this activity, or ever publicly denouncing the KKK, which was initially founded in 1866 for the specific purpose of terrorizing freed Blacks.

Maybe it’s time to finally say good bye to the Lee Monument— not to erase history — but to embrace it, because Robert E Lee probably should have never been put on that pedestal in the first place.