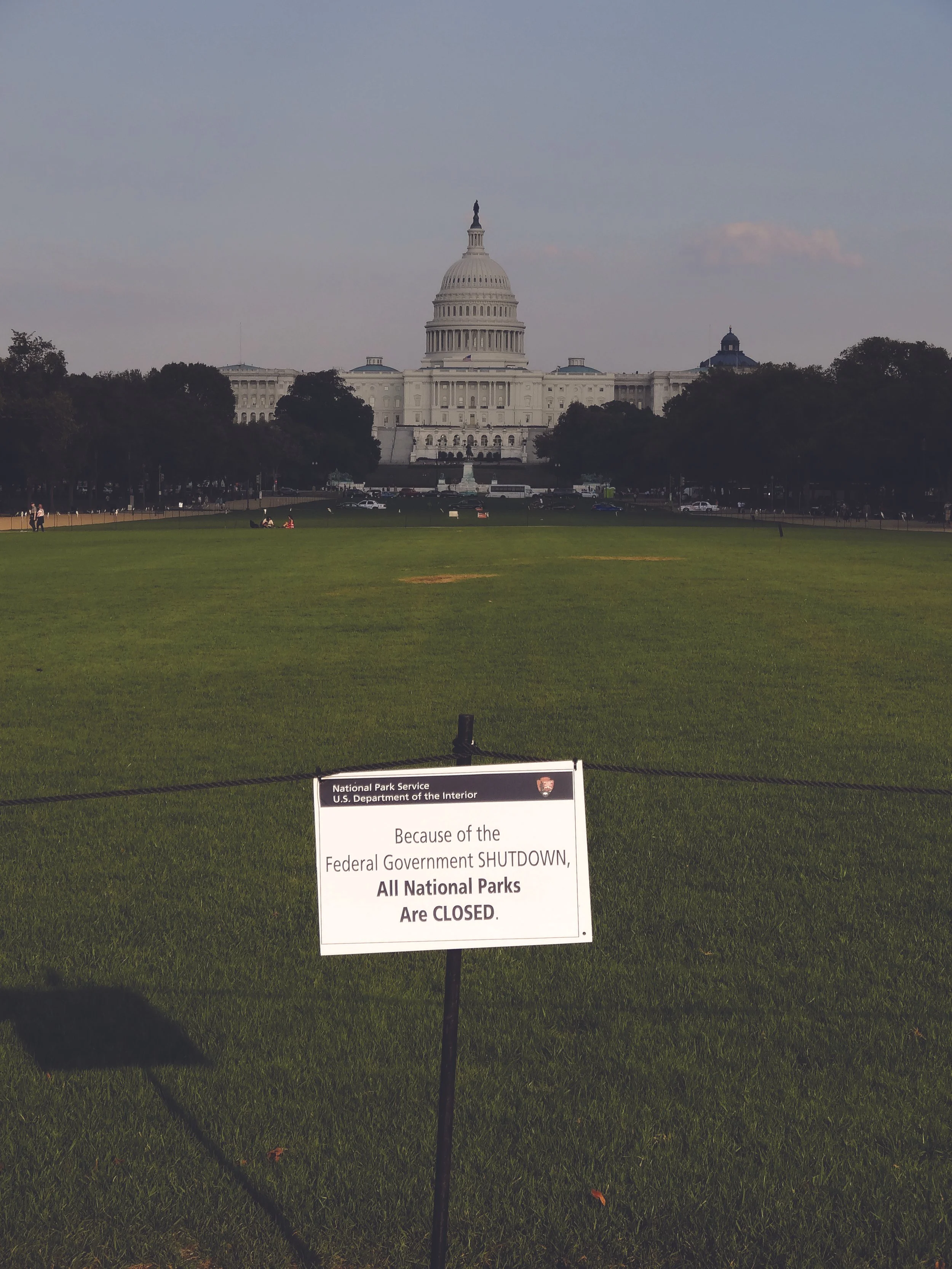

The lawn of National Mall with US Capitol in the background. The lawn was gated and closed during the US government shutdown of 2013. Photo by Emw on Wikipedia Commons; this image is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

US Healthcare and the Government Shut Down

by Jack R Johnson 10.2025

To understand the current government shut down over subsidizing Obamacare, start with a small pox outbreak in the late 1860s. That’s when an epidemic “hopscotched” across the post-Civil War South, invading the makeshift camps where many thousands of newly freed African-Americans had taken refuge.

According to the New York Times, “White leaders were deeply ambivalent about intervening [...] White legislators argued that free assistance of any kind would breed dependence and that when it came to black infirmity, hard labor was a better salve than white medicine. As the death toll rose, they developed a new theory: Blacks were so ill-suited to freedom that the entire race was going extinct. “No charitable black scheme can wash out the color of the Negro, change his inferior nature or save him from his inevitable fate,” said Ohio Congressman Samuel S. Cox. It was an attitude that would shape the healthcare debate for generations to come.

On May 1896, the evident cruelty of Cox’s statement was given a scientific gloss. Frederick L. Hoffman, a statistician at the Prudential Life Insurance Company published a 330-page article entitled Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro in the prestigious Publications of the American Economic Association intended to prove—with statistical reliability—that the American Negro was uninsurable.

According to Megan J. Wolfe, writing for The National Library of Medicine, “Race Traits immediately became a key text in one of the central social preoccupations of the turn of the century: the supposed Negro Problem. Numerous turn-of-the-century tracts (including Hoffman's) stipulated that minority racial groups were not only biologically inferior but also barriers to progress. Hoffman, a German immigrant, was one of the leading statisticians of his time and also a strong proponent of racial hierarchy and white supremacy.”

In 1915, Hoffman promoted what came to be known as the “racial extinction theory,” a belief that Black Americans had less “ability to maintain individual life.” Providing Black Americans with health care would only postpone their inevitable decline or “gradual extinction,” Hoffman argued, and thus work against the “natural order.”

In his 1896 book Race Traits, Hoffman laid out his “scientific” assertion that when government steps in to help people, it invariably ends up hurting them instead. According to Thomas Hartmann, Hoffman and Prudential Insurance weren’t merely racists; they were against any American receiving government funded universal healthcare.

In 1916, the American Association for Labor Legislation (AALL) endorsed health insurance provided through a network of local and statewide mutual companies and called for those policies to also provide a small death benefit to cover funeral costs, which would have competed directly with the funeral coverage that was Prudential’s main cash cow. Hoffman wrote to the company, “We, of course, cannot compete with Compulsory Insurance, including a death benefit of, say $100.” He then began a campaign, sponsored by Prudential, to stop state-funded health insurance. Frederick Hoffman became the most well-known face of a massive, multiyear effort to stop the AALL’s campaign. He was remarkably effective. Hartmann writes that “Hoffman’s Prudential-sponsored campaign to prevent any state from adopting a statewide nonprofit health (and death benefit) insurance program went into overdrive through 1916–1920. In 1920, in large part because of Prudential’s efforts and Hoffman’s warnings, California’s voters resoundingly turned down a voter initiative in that state to provide health insurance, and, although New York’s Senate passed the bill, it died in committee in the Assembly.”

Even while state led efforts were being defeated, there were national drives for universal healthcare reform complicated by racist concerns. In 1945, when President Truman called on Congress to expand the nation’s hospital system as part of a larger health care plan, Southern Democrats balked at integrated hospitals and demanded as a key concession separate facilities—one for whites and another for blacks. The New York Times noted that “professional societies like the American Medical Association barred black doctors; medical schools excluded black students, and most hospitals and health clinics segregated black patients. Federal health care policy was designed, both implicitly and explicitly, to exclude black Americans.”

Finally, a century after smallpox ripped through the freeman’s quarters mostly untreated, the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed segregation for any entity receiving federal funds. Newly passed health care programs—Medicare and Medicaid—soon placed every hospital in the country in that category.

Medicare started on July 30, 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965. The program was created to address a significant lack of affordable healthcare for older Americans. Another joint federal and state program, Medicaid provided health insurance coverage for more than 72 million people, including low-income Americans and their children and people with disabilities. It also helped foot the bill for long-term care for older people. In the absence of a universal health care system, Medicaid filled many of the gaps left by private insurance, but it still excluded millions of Americans based on income and employment.

Enter Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in 2010. That act brought health insurance to nearly 20 million previously uninsured adults. According to the Atlantic magazine, “The ACA lowered the uninsurance rate from 16 to 8 percent, granting Medicaid to 20 million people and defraying costs for an additional 22 million as of this year. It also pushed expenses down overall. National health spending went from growing 6.9 percent a year before the law passed to 4.3 percent a year after. The share of the economy devoted to medical care stopped rising. The rate of inflation in the health-care sector slowed, even as Americans received more care. The Congressional Budget Office’s projections of future Medicare spending declined “dramatically.” According to the New York Times, “the biggest beneficiaries were people of color, many of whom obtained coverage through the law’s Medicaid expansion.”

In late February 2025, House Republicans approved a budget proposal (The Big Beautiful Bill) that cut $880 billion from Medicaid over 10 years. President Donald Trump backed the budget despite repeatedly vowing on the campaign trail that Medicaid was off the table.

Now, cuts to Medicaid and the ACA legislative package are the main reasons the federal government remains shut down. In exchange for their votes, Senate Democrats are demanding that the GOP roll back its Medicaid cuts and preserve insurance subsidies used by 20 million Americans. Without those subsidies, a person earning $28,000 a year will go from paying $325 a year for health coverage to paying $1,562. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the cuts will result in 11.8 million individuals directly losing their health insurance coverage under Medicaid, and an additional roughly 3.1 million people losing Medicaid coverage under marketplace plans

This hits our poorest populations the hardest while billionaires are receiving unneeded tax cuts. Not surprisingly, a majority of those most adversely affected by the cuts will likely be minorities. It’s a long standing U.S. tradition.